Relics of the Passion

Veith has a beautiful thought in the beginning of his little book on the Instruments of Christ’s Passion: as, in the lovely regions of the East, friends send to one another, as pledges of affection, nosegays in which each flower has its appropriate meaning, so does our Jesus reach out to us from the Holy Land a bouquet made of the instruments of His Passion, as a token of His everlasting Love.

The hand of time, acting in obedience to our Lord’s Will, has scattered the various flowers of the nosegay in different gardens of the Church. Some bloom round the foot of Peter’s Chair, some on the banks of the Moselle, some on the sunny Seine. Let us unite them again in spirit, and put them in our hearts, that their sweet fragrance may attract the Heavenly Gardener into our souls.

The Crown of Thorns

The cruel soldiers, after they had scourged our Lord, placed on His Sacred Head a crown of thorns. The Evangelists do not tell us whether Jesus bore His diadem of shame and torture to Calvary, and whether it was on His Head when He hung on the Cross; but the pious belief of the faithful and the traditions of Christian art agree on both these points. The disciples who took down the Sacred Body from the Cross took possession of the crown of thorns. The Christians of the first century kept it with great reverence, and handed it down to the second generation. Saint Paulinus of Nola tells us, in 409, that the crown of thorns was then in the possession of the faithful. Like most of the relics of the Passion it became the property of the imperial treasury of Constantinople. There it remained until the thirteenth century, when the Latin emperors, being in want of money, pawned it and other relics to the Venetians. Baldwin II relinquished his claim to these holy articles in favour of Saint Louis, King of France. The holy monarch immediately redeemed them, and conveyed them with all honour to the chapel of his royal palace in Paris. The crown of thorns was taken from its reliquary in 1793, during the first French Revolution, and broken into three pieces, which were taken, with the other relics of the Sacred Chapel, to the Commission of Arts, and thence to the National Library. In 1804, Cardinal de Bellay, Archbishop of Paris, begged that the articles should be restored to the cathedral, and his petition was granted. The crown was identified by those who had seen and examined it before its seizure by the government. There are now no thorns on it, these having been given away as relics to different churches.

The cruel soldiers, after they had scourged our Lord, placed on His Sacred Head a crown of thorns. The Evangelists do not tell us whether Jesus bore His diadem of shame and torture to Calvary, and whether it was on His Head when He hung on the Cross; but the pious belief of the faithful and the traditions of Christian art agree on both these points. The disciples who took down the Sacred Body from the Cross took possession of the crown of thorns. The Christians of the first century kept it with great reverence, and handed it down to the second generation. Saint Paulinus of Nola tells us, in 409, that the crown of thorns was then in the possession of the faithful. Like most of the relics of the Passion it became the property of the imperial treasury of Constantinople. There it remained until the thirteenth century, when the Latin emperors, being in want of money, pawned it and other relics to the Venetians. Baldwin II relinquished his claim to these holy articles in favour of Saint Louis, King of France. The holy monarch immediately redeemed them, and conveyed them with all honour to the chapel of his royal palace in Paris. The crown of thorns was taken from its reliquary in 1793, during the first French Revolution, and broken into three pieces, which were taken, with the other relics of the Sacred Chapel, to the Commission of Arts, and thence to the National Library. In 1804, Cardinal de Bellay, Archbishop of Paris, begged that the articles should be restored to the cathedral, and his petition was granted. The crown was identified by those who had seen and examined it before its seizure by the government. There are now no thorns on it, these having been given away as relics to different churches.

The Church celebrates the Festival of the Crown of Thorns on the Friday after Ash-Wednesday. The office is full of the most beautiful and touching sentiments, which could have sprung from no other heart than that of Christ’s Mystic Spouse. Thus she addresses the virgins of Jerusalem in the hymn of Vespers:

Go ye forth! O Sion’s daughters!

See the thorny coronet

On the temples of your Saviour

By a cruel mother set.

Seek in vain for rays of glory

Streaming from His forehead now:

Thorns, in needles long and piercing,

Bristle round His blood-stained brow.

Cruel earth! of thorns and brambles,

Such a woeful crop to bear:

Cruel hand! to pluck and wreath them

In the looks of Jesus’ hair.

See, the thorn-bush blooms in roses!

Fed by blood-drops of the Lamb;

And the thorn is victory’s emblem,

Like the laurel and the palm.

Than the thorns that wreathed His temples

Far more cruel is the smart

Unto Jesus of the brambles

That are growing in man’s heart.

Pluck them, Saviour, from our bosoms,

Sin did plant them, they have grown;

And in place of them, sweet Jesus,

Plant the memory of Thine own.

The hymn of Lauds enumerates the types of our Saviour’s crown contained in the Old Testament.

In the Law are types and figures

Of the painful crown of Christ;

First, the thorn-entangled victim

By the Patriarch sacrificed.

On the fiery bush of Horeb

Ponder, Christians; from it learn

How amid Christ’s thorny circlet

Flames of pure love ruddy burn.

And around the Ark, as emblem,

Was a crown of purest gold,

And around the incense altar

Were the clouds of fragrance rolled.

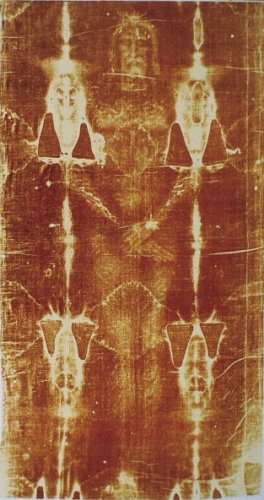

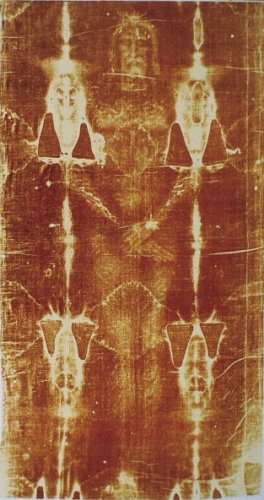

The Holy Shroud

We learn from the Gospel according to Saint John that several linen cloths were wrapped around the Body of our Lord when It was laid in the tomb. They took therefore, the Body of Jesus, and bound It in linen cloths with the slices, as it is the custom with the Jews to bury…. Then cometh Simon Peter, following him, and went into the sepulchre, and saw the linen cloths lying. (John 19:40; 20:6) Hence, there is no difficulty in reconciling the traditions of different churches, as of Turin, Besancon, etc., that they are in possession of the true shroud of our Lord; each may have one of the several which touched His Sacred Corpse. That of Turin is the most celebrated; it has the marks of the wounds and of the Blood. Nicodemus, who assisted Joseph of Arirmathea in burying our Lord, was the first possessor of this holy shroud. When he was dying he bequeathed it to Gamaliel, the great Doctor of the Pharisees and teacher of Saint Paul. Gamaliel transmitted it to Saint James the Less, the first Bishop of Jerusalem, and he to his successor, Saint Simeon. Thus it passed from hand to hand among the Christians of Jerusalem, until the city was captured, in 1187, by Saladin, when Guy of Lusignan, the dethroned King of Jerusalem, going to Cyprus, which had been ceded to him by Richard of England, took the relic with him. In 1450, tho Princess Margaret, the widow of the last of the Lusignans, fearing that she might fall into the hands of the Turks, resolved to go to France. She took the holy shroud with her, and when she passed through Chambery to visit her relative, the Duchess of Savoy, she made her a present of it From Chambery the holy shroud was carried to Annecy, and thence to Turin, the capital of Sardinia, where it is now. It was in presence of this precious memorial of the Passion that the mother of Saint Francis of Sales made an offering of her son, yet unborn, to Jesus Christ.

We learn from the Gospel according to Saint John that several linen cloths were wrapped around the Body of our Lord when It was laid in the tomb. They took therefore, the Body of Jesus, and bound It in linen cloths with the slices, as it is the custom with the Jews to bury…. Then cometh Simon Peter, following him, and went into the sepulchre, and saw the linen cloths lying. (John 19:40; 20:6) Hence, there is no difficulty in reconciling the traditions of different churches, as of Turin, Besancon, etc., that they are in possession of the true shroud of our Lord; each may have one of the several which touched His Sacred Corpse. That of Turin is the most celebrated; it has the marks of the wounds and of the Blood. Nicodemus, who assisted Joseph of Arirmathea in burying our Lord, was the first possessor of this holy shroud. When he was dying he bequeathed it to Gamaliel, the great Doctor of the Pharisees and teacher of Saint Paul. Gamaliel transmitted it to Saint James the Less, the first Bishop of Jerusalem, and he to his successor, Saint Simeon. Thus it passed from hand to hand among the Christians of Jerusalem, until the city was captured, in 1187, by Saladin, when Guy of Lusignan, the dethroned King of Jerusalem, going to Cyprus, which had been ceded to him by Richard of England, took the relic with him. In 1450, tho Princess Margaret, the widow of the last of the Lusignans, fearing that she might fall into the hands of the Turks, resolved to go to France. She took the holy shroud with her, and when she passed through Chambery to visit her relative, the Duchess of Savoy, she made her a present of it From Chambery the holy shroud was carried to Annecy, and thence to Turin, the capital of Sardinia, where it is now. It was in presence of this precious memorial of the Passion that the mother of Saint Francis of Sales made an offering of her son, yet unborn, to Jesus Christ.

The Lance

Among the relics which Saint Louis redeemed from the Venetians was the point of the lance which pierced our Saviour’s side. The handle remained at Constantinople until the end of the fifteenth century, when it was sent by the Sultan Bajazet as a present to Pope Innocent VIII. It is now preserved with great veneration in the Vatican Basilica.

Among the relics which Saint Louis redeemed from the Venetians was the point of the lance which pierced our Saviour’s side. The handle remained at Constantinople until the end of the fifteenth century, when it was sent by the Sultan Bajazet as a present to Pope Innocent VIII. It is now preserved with great veneration in the Vatican Basilica.

It is the more common opinion of ecclesiastical antiquarians, that it was our Lord’s right side that was pierced by the lance. Hence those paintings which represent the left side as wounded are not in accordance with the traditions of Christian art.

The soldier who pierced Jesus is venerated in the Western or Latin Church under the name of Saint Longinus. After the Crucifixion he became a Christian, and preached the faith in Cappodocia, a province of Asia, where he was crowned with martyrdom. There is a legend that, having casually applied to his eyes his hands stained with the Blood which trickled down from the sacred wound, he was immediately freed from a weakness of sight with which he was affected.

The Nails

It is certain that our Lord was fastened to the Cross with nails and not with ropes. Thus speaks the Apostle Saint Thomas, whose doubts serve to confirm our faith: Except I shall see in His hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the place of the nails, and put my hand into His tide, I will not believe. (John 20:25) The nails are clearly alluded to in the prophecy of our Saviour’s Passion, Contained in the 21st Psalm: They have dug My hands and feet.

It is certain that our Lord was fastened to the Cross with nails and not with ropes. Thus speaks the Apostle Saint Thomas, whose doubts serve to confirm our faith: Except I shall see in His hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the place of the nails, and put my hand into His tide, I will not believe. (John 20:25) The nails are clearly alluded to in the prophecy of our Saviour’s Passion, Contained in the 21st Psalm: They have dug My hands and feet.

The Sacred Body was pierced with four nails, each foot having its separate nail. No bone of our Saviour was broken, and this could scarcely have happened, says Benedict XIV, had one nail been made to pass through both feet.

“According to the opinion more generally adopted,” says Abbe Guillois in his Catechism, “the arms of our Lord, when attached to the cross, were nearly horizontal, to show that His love was universal, embracing the whole human race. The Jansenists, who hold that Jesus Christ did not die for all men, represent the arms in a position more or less vertical. Crucifixes of this kind have been called Jansenistic crucifixes.”

The nails were found by Saint Helena at the same time that she discovered the Cross. The pious empress attached one to the helmet of Constantine her son, and another to the bridle of his horse. It is commonly said that she threw a third into the Adriatic Sea in order to appease the tempests which so frequently lashed it into fury. But it is not probable that she would so readily cast away so precious a relic: may she not have simply dipped it into the waves?

A part of one of the nails is in the church of the Holy Cross at Rome, The Cathedrals of Paris, Treves, and Toul, are in possession of others. Filings from the true nails, and nails which have touched them, are kept in different churches as relics.

The celebrated Iron Crown of Italy contains a portion of one of the sacred nails.

The Title of the Cross

And Pilate wrote a title also: and put it upon the cross. And the writing was, Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews….and it was written in Hebrew, in Greek, and in Latin. (John 19:19,20) Hebrew, or as it was then called, Syro-Chaidaic, was the language of the great multitude of the Jews; yet those who lived dispersed through the provinces of the former Graeco-Macedonian empire were more conversant with Greek, and as there were many of them in Jerusalem at the time of the Crucifixion, because of the Pasch, the title was written in Greek that they might read it. Latin was the official language of the government.

And Pilate wrote a title also: and put it upon the cross. And the writing was, Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews….and it was written in Hebrew, in Greek, and in Latin. (John 19:19,20) Hebrew, or as it was then called, Syro-Chaidaic, was the language of the great multitude of the Jews; yet those who lived dispersed through the provinces of the former Graeco-Macedonian empire were more conversant with Greek, and as there were many of them in Jerusalem at the time of the Crucifixion, because of the Pasch, the title was written in Greek that they might read it. Latin was the official language of the government.

Saint Ambrose and Rufinus relate that Saint Helena found the title, but in a different place from that in which she found the cross. She presented it to the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Rome. Peter Gonsalvo, Cardinal de Mendoza, tells us that when this church was undergoing repairs in 1482, under Pope Innocent VIII, a part of the title of the cross, inscribed with Hebrew, Greek, and Latin characters, was found in the wall. The last two letters of the word Judaeorum were wanting. When the sacred relic was examined again in 1564, 1648, and 1828, the ravages of time on the letters were still more visible. No more remains of the Hebrew inscription than the terminations of some letters which can no longer be deciphered. Of the Greek inscription the word Nazarenous remains The Latin is a little more complete, containing, beside the adjective Nazarenus, the two first letters of the word Rex. These remains show us that the Greek and Latin letters were written, contrary to the usual custom, from right to left. This was done in order to make them correspond with the first inscription, which was in Hebrew: this language is always written from right to left.

The Seamless Robe

The seamless robe which our Lord wore was, according to many writers, the work of the Blessed Virgin. She wove it with her own hands, and clothed her Son with it while He was still a child. The tunic grew with the growth of Jesus Christ, and never wore out; a miracle the like of which God had already wrought in favour of the Jews in their passage through the desert of Arabia to the Promised Land. During the forty years of their journey their garments wore not out. (Deuteronomy 29:5) The Evangelist Saint John (19:23,24) thus relates what happened to the seamless robe on Calvary: Then the soldiers, when they had crucified Him, took His garments (and they made four parts, to every soldier a part) and also His coat. Now the coat was without seam, woven from the top throughout. They said then one to another: Let us not cut it; but let us cast lots for it whose it shall be And the soldiers indeed did these things. The holy tunic was redeemed by the Christians, and came into possession of Saint Helena when she went to the Holy Land. On her return to Europe she gave it to Agricius, Bishop of Treves, a city on the banks of the Moselle.

The seamless robe which our Lord wore was, according to many writers, the work of the Blessed Virgin. She wove it with her own hands, and clothed her Son with it while He was still a child. The tunic grew with the growth of Jesus Christ, and never wore out; a miracle the like of which God had already wrought in favour of the Jews in their passage through the desert of Arabia to the Promised Land. During the forty years of their journey their garments wore not out. (Deuteronomy 29:5) The Evangelist Saint John (19:23,24) thus relates what happened to the seamless robe on Calvary: Then the soldiers, when they had crucified Him, took His garments (and they made four parts, to every soldier a part) and also His coat. Now the coat was without seam, woven from the top throughout. They said then one to another: Let us not cut it; but let us cast lots for it whose it shall be And the soldiers indeed did these things. The holy tunic was redeemed by the Christians, and came into possession of Saint Helena when she went to the Holy Land. On her return to Europe she gave it to Agricius, Bishop of Treves, a city on the banks of the Moselle.

The church of Argenteuil, near Paris, possesses another garment of our Lord, the authenticity of which has been established by many signal favours of heaven. The Lady Superior of Les Dames de Saint Louis, at Juilly, diocese of Meaux, writing to the curate of Argenteuil, under date of 2nd of January, 1847, testifies that she had been completely cured of a disease in the knee, by a novena in honour of the holy robe of Argenteuil.

The Bishop of Treves, whose cathedral possesses the seamless robe, obtained in 1844, the institution of an office in honour of this relic. A prodigious multitude of pilgrims – according to some accounts two millions in number – flocked during that year to Treves, to reverence this memorial of our Lord and the Blessed Virgin.

- taken from The Sacramentals of the Holy Catholic Church, by Father William James Barry

The cruel soldiers, after they had scourged our Lord, placed on His Sacred Head a crown of thorns. The Evangelists do not tell us whether Jesus bore His diadem of shame and torture to Calvary, and whether it was on His Head when He hung on the Cross; but the pious belief of the faithful and the traditions of Christian art agree on both these points. The disciples who took down the Sacred Body from the Cross took possession of the crown of thorns. The Christians of the first century kept it with great reverence, and handed it down to the second generation. Saint Paulinus of Nola tells us, in 409, that the crown of thorns was then in the possession of the faithful. Like most of the relics of the Passion it became the property of the imperial treasury of Constantinople. There it remained until the thirteenth century, when the Latin emperors, being in want of money, pawned it and other relics to the Venetians. Baldwin II relinquished his claim to these holy articles in favour of Saint Louis, King of France. The holy monarch immediately redeemed them, and conveyed them with all honour to the chapel of his royal palace in Paris. The crown of thorns was taken from its reliquary in 1793, during the first French Revolution, and broken into three pieces, which were taken, with the other relics of the Sacred Chapel, to the Commission of Arts, and thence to the National Library. In 1804, Cardinal de Bellay, Archbishop of Paris, begged that the articles should be restored to the cathedral, and his petition was granted. The crown was identified by those who had seen and examined it before its seizure by the government. There are now no thorns on it, these having been given away as relics to different churches.

The cruel soldiers, after they had scourged our Lord, placed on His Sacred Head a crown of thorns. The Evangelists do not tell us whether Jesus bore His diadem of shame and torture to Calvary, and whether it was on His Head when He hung on the Cross; but the pious belief of the faithful and the traditions of Christian art agree on both these points. The disciples who took down the Sacred Body from the Cross took possession of the crown of thorns. The Christians of the first century kept it with great reverence, and handed it down to the second generation. Saint Paulinus of Nola tells us, in 409, that the crown of thorns was then in the possession of the faithful. Like most of the relics of the Passion it became the property of the imperial treasury of Constantinople. There it remained until the thirteenth century, when the Latin emperors, being in want of money, pawned it and other relics to the Venetians. Baldwin II relinquished his claim to these holy articles in favour of Saint Louis, King of France. The holy monarch immediately redeemed them, and conveyed them with all honour to the chapel of his royal palace in Paris. The crown of thorns was taken from its reliquary in 1793, during the first French Revolution, and broken into three pieces, which were taken, with the other relics of the Sacred Chapel, to the Commission of Arts, and thence to the National Library. In 1804, Cardinal de Bellay, Archbishop of Paris, begged that the articles should be restored to the cathedral, and his petition was granted. The crown was identified by those who had seen and examined it before its seizure by the government. There are now no thorns on it, these having been given away as relics to different churches. We learn from the Gospel according to Saint John that several linen cloths were wrapped around the Body of our Lord when It was laid in the tomb. They took therefore, the Body of Jesus, and bound It in linen cloths with the slices, as it is the custom with the Jews to bury…. Then cometh Simon Peter, following him, and went into the sepulchre, and saw the linen cloths lying. (John 19:40; 20:6) Hence, there is no difficulty in reconciling the traditions of different churches, as of Turin, Besancon, etc., that they are in possession of the true shroud of our Lord; each may have one of the several which touched His Sacred Corpse. That of Turin is the most celebrated; it has the marks of the wounds and of the Blood. Nicodemus, who assisted Joseph of Arirmathea in burying our Lord, was the first possessor of this holy shroud. When he was dying he bequeathed it to Gamaliel, the great Doctor of the Pharisees and teacher of Saint Paul. Gamaliel transmitted it to Saint James the Less, the first Bishop of Jerusalem, and he to his successor, Saint Simeon. Thus it passed from hand to hand among the Christians of Jerusalem, until the city was captured, in 1187, by Saladin, when Guy of Lusignan, the dethroned King of Jerusalem, going to Cyprus, which had been ceded to him by Richard of England, took the relic with him. In 1450, tho Princess Margaret, the widow of the last of the Lusignans, fearing that she might fall into the hands of the Turks, resolved to go to France. She took the holy shroud with her, and when she passed through Chambery to visit her relative, the Duchess of Savoy, she made her a present of it From Chambery the holy shroud was carried to Annecy, and thence to Turin, the capital of Sardinia, where it is now. It was in presence of this precious memorial of the Passion that the mother of Saint Francis of Sales made an offering of her son, yet unborn, to Jesus Christ.

We learn from the Gospel according to Saint John that several linen cloths were wrapped around the Body of our Lord when It was laid in the tomb. They took therefore, the Body of Jesus, and bound It in linen cloths with the slices, as it is the custom with the Jews to bury…. Then cometh Simon Peter, following him, and went into the sepulchre, and saw the linen cloths lying. (John 19:40; 20:6) Hence, there is no difficulty in reconciling the traditions of different churches, as of Turin, Besancon, etc., that they are in possession of the true shroud of our Lord; each may have one of the several which touched His Sacred Corpse. That of Turin is the most celebrated; it has the marks of the wounds and of the Blood. Nicodemus, who assisted Joseph of Arirmathea in burying our Lord, was the first possessor of this holy shroud. When he was dying he bequeathed it to Gamaliel, the great Doctor of the Pharisees and teacher of Saint Paul. Gamaliel transmitted it to Saint James the Less, the first Bishop of Jerusalem, and he to his successor, Saint Simeon. Thus it passed from hand to hand among the Christians of Jerusalem, until the city was captured, in 1187, by Saladin, when Guy of Lusignan, the dethroned King of Jerusalem, going to Cyprus, which had been ceded to him by Richard of England, took the relic with him. In 1450, tho Princess Margaret, the widow of the last of the Lusignans, fearing that she might fall into the hands of the Turks, resolved to go to France. She took the holy shroud with her, and when she passed through Chambery to visit her relative, the Duchess of Savoy, she made her a present of it From Chambery the holy shroud was carried to Annecy, and thence to Turin, the capital of Sardinia, where it is now. It was in presence of this precious memorial of the Passion that the mother of Saint Francis of Sales made an offering of her son, yet unborn, to Jesus Christ. Among the relics which Saint Louis redeemed from the Venetians was the point of the lance which pierced our Saviour’s side. The handle remained at Constantinople until the end of the fifteenth century, when it was sent by the Sultan Bajazet as a present to Pope Innocent VIII. It is now preserved with great veneration in the Vatican Basilica.

Among the relics which Saint Louis redeemed from the Venetians was the point of the lance which pierced our Saviour’s side. The handle remained at Constantinople until the end of the fifteenth century, when it was sent by the Sultan Bajazet as a present to Pope Innocent VIII. It is now preserved with great veneration in the Vatican Basilica. It is certain that our Lord was fastened to the Cross with nails and not with ropes. Thus speaks the Apostle Saint Thomas, whose doubts serve to confirm our faith: Except I shall see in His hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the place of the nails, and put my hand into His tide, I will not believe. (John 20:25) The nails are clearly alluded to in the prophecy of our Saviour’s Passion, Contained in the 21st Psalm: They have dug My hands and feet.

It is certain that our Lord was fastened to the Cross with nails and not with ropes. Thus speaks the Apostle Saint Thomas, whose doubts serve to confirm our faith: Except I shall see in His hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the place of the nails, and put my hand into His tide, I will not believe. (John 20:25) The nails are clearly alluded to in the prophecy of our Saviour’s Passion, Contained in the 21st Psalm: They have dug My hands and feet. And Pilate wrote a title also: and put it upon the cross. And the writing was, Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews….and it was written in Hebrew, in Greek, and in Latin. (John 19:19,20) Hebrew, or as it was then called, Syro-Chaidaic, was the language of the great multitude of the Jews; yet those who lived dispersed through the provinces of the former Graeco-Macedonian empire were more conversant with Greek, and as there were many of them in Jerusalem at the time of the Crucifixion, because of the Pasch, the title was written in Greek that they might read it. Latin was the official language of the government.

And Pilate wrote a title also: and put it upon the cross. And the writing was, Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews….and it was written in Hebrew, in Greek, and in Latin. (John 19:19,20) Hebrew, or as it was then called, Syro-Chaidaic, was the language of the great multitude of the Jews; yet those who lived dispersed through the provinces of the former Graeco-Macedonian empire were more conversant with Greek, and as there were many of them in Jerusalem at the time of the Crucifixion, because of the Pasch, the title was written in Greek that they might read it. Latin was the official language of the government. The seamless robe which our Lord wore was, according to many writers, the work of the Blessed Virgin. She wove it with her own hands, and clothed her Son with it while He was still a child. The tunic grew with the growth of Jesus Christ, and never wore out; a miracle the like of which God had already wrought in favour of the Jews in their passage through the desert of Arabia to the Promised Land. During the forty years of their journey their garments wore not out. (Deuteronomy 29:5) The Evangelist Saint John (19:23,24) thus relates what happened to the seamless robe on Calvary: Then the soldiers, when they had crucified Him, took His garments (and they made four parts, to every soldier a part) and also His coat. Now the coat was without seam, woven from the top throughout. They said then one to another: Let us not cut it; but let us cast lots for it whose it shall be And the soldiers indeed did these things. The holy tunic was redeemed by the Christians, and came into possession of Saint Helena when she went to the Holy Land. On her return to Europe she gave it to Agricius, Bishop of Treves, a city on the banks of the Moselle.

The seamless robe which our Lord wore was, according to many writers, the work of the Blessed Virgin. She wove it with her own hands, and clothed her Son with it while He was still a child. The tunic grew with the growth of Jesus Christ, and never wore out; a miracle the like of which God had already wrought in favour of the Jews in their passage through the desert of Arabia to the Promised Land. During the forty years of their journey their garments wore not out. (Deuteronomy 29:5) The Evangelist Saint John (19:23,24) thus relates what happened to the seamless robe on Calvary: Then the soldiers, when they had crucified Him, took His garments (and they made four parts, to every soldier a part) and also His coat. Now the coat was without seam, woven from the top throughout. They said then one to another: Let us not cut it; but let us cast lots for it whose it shall be And the soldiers indeed did these things. The holy tunic was redeemed by the Christians, and came into possession of Saint Helena when she went to the Holy Land. On her return to Europe she gave it to Agricius, Bishop of Treves, a city on the banks of the Moselle.