"A rich man had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property. He summoned him and said, 'What is this I hear about you? Prepare a full account of your stewardship, because you can no longer be my steward.'

"A rich man had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property. He summoned him and said, 'What is this I hear about you? Prepare a full account of your stewardship, because you can no longer be my steward.' "A rich man had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property. He summoned him and said, 'What is this I hear about you? Prepare a full account of your stewardship, because you can no longer be my steward.'

"A rich man had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property. He summoned him and said, 'What is this I hear about you? Prepare a full account of your stewardship, because you can no longer be my steward.'

"The steward said to himself, 'What shall I do, now that my master is taking the position of steward away from me? I am not strong enough to dig and I am ashamed to beg. I know what I shall do so that, when I am removed from the stewardship, they may welcome me into their homes.'

"He called in his master's debtors one by one. To the first he said, 'How much do you owe my master?'

"He replied, 'One hundred measures of olive oil.'

"He said to him, 'Here is your promissory note. Sit down and quickly write one for fifty.'

"Then to another he said, 'And you, how much do you owe?'

"He replied, 'One hundred kors of wheat.'

"He said to him, 'Here is your promissory note; write one for eighty.'

"And the master commended that dishonest steward for acting prudently. For the children of this world are more prudent in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light. I tell you, make friends for yourselves with dishonest wealth, so that when it fails, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings. The person who is trustworthy in very small matters is also trustworthy in great ones; and the person who is dishonest in very small matters is also dishonest in great ones. If, therefore, you are not trustworthy with dishonest wealth, who will trust you with true wealth? If you are not trustworthy with what belongs to another, who will give you what is yours?"

- Luke 16:1-12

The New Testament teaches us both by word and example what the Christian character should be. Our Lord came 'to be unto us an example of godly life.' In all difficulties we look to Him as an unfailing guide. What He did was always the best and the most perfect. The Old Testament taught by precepts - 'Thou shalt, thou shalt not' It went into minute details as regards religious and social life, and its followers felt the burden of the law, and many of them got entangled in its meshes. It could not make the comers thereunto perfect.

Christ came, and instead of precepts and prohibitions there stood before men a living Person, and He summed up all that the Law had said, and a great deal more, in a few words, 'If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell all that thou hast and give unto the poor, and come and follow Me!' (Matthew 19:21) Christ stood before men and won their hearts, and as, loving Him, they sought to be like Him, they became transformed. They had not to ask themselves under different circumstances, 'What is written?' 'What is commanded?' but 'What would this Person, whom I love above all, have done under these same circumstances?' He set men free from the Law, though He brought them under a far stricter and more searching law, by winning their love. As they loved the Lawgiver, all the burden of obedience was removed.

What a difference there is between the character and spirit of the Jew striving to obey a law written upon tables of stone, and a Christian obeying the law of Jesus Christ The Jew finds himself face to face with precepts that never change, that were written down once for all upon the tables of stone, as cold, as hard, as unbending as the stone upon which they were written, 'This do and ye shall live.' There was ^nothing personal, no touch of sympathy, no power of adaptability. If they failed it frowned upon them in its coldness and condemned them. They could not make terms with it, they could not induce it to bend to any special considerations of difficulty, or temperament, or weakness. 'By the Law is the knowledge of sin.' (Romans 3:20)

How different from all this is the condition of the Christian. The Lawgiver Himself comes down amidst all the circumstances of human life and lives out the law in all its perfection. He goes before, showing the way, and bids us follow Him, and as our love for Him grows stronger we find that the Law, indeed, penetrates more searchingly into the recesses of the heart and mind, to rule and discipline and cleanse them, but our personal love for Him makes all easy. The Christian finds His law possessed of all that power of adaptability and adjustment and elasticity that arises from its being set before him in the form of a personal life rather than upon tables of stone. 'The letter killeth, the spirit giveth life.' (2 Corinthians 3:6) The old law was the letter, written and unchangeable, it killed. The new law revealed itself in a living character, and it giveth life.

And as we study His Character and read His words we can have no doubt what kind of character the Christian's should be. We may explain away words, but we cannot explain away character. He stood forth before the world a new Revelation. He brought to light a new side of our nature, never, or but dimly, seen before. He set before us a new class of virtue, and pointed out the principle of evil lurking in the most unexpected places. He laid down certain ruling principles that were to govern and to form the Christian character, and in His own sacred Person He showed those principles at work. 'Jesus began both to do and to teach.' (Acts 1:1) His teaching was, to a certain extent, a Revelation of His own inner Life. As those who lived nearest to Him heard the Sermon on the Mount, they would know that He was putting into words what they had seen Him portray in action.

And His Character and His teaching might be summed up in one word, as, being above everything else, unworldly. 'Let this mind be in you,' says the Apostle, 'which was also in Christ Jesus, who, being in the Form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God; but made Himself of no reputation, and took upon Him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men, and being found in the fashion of a man. He humbled Himself.' (Philippians 2:5-8) 'Love not the world,' said the Apostle who leant upon His Breast at the Last Supper, 'neither the things that are in the world. If any man love the world the love of the Father is not in him.' (1 John 2:15) There is no Christian virtue all through the Gospels that does not help to add some deeper tone to this the chief and most marked feature of His Character. Each one of the Beatitudes is but another, and yet another, development of the unworldly spirit They begin with that virtue which most separates men from the world, and they end with the world's antagonism formulated in violence and persecution.

Step by step, as the Christian life develops, it is marked by an advance in the spirit of unworldliness.

As our Lord's teaching advances we see in a hundred different ways this same spirit is inculcated. Heavenly-mindedness, the love of God, must beget unworldliness; and conversely, those who give up more and more of what nourishes the worldly spirit will become more heavenly-minded. 'Resist not evil, but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek turn to him the other also.' (Matthew 5:39,40) 'If any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also.' (Matthew 5:39,40) 'Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you and persecute you.' (Matthew 5:44)

No person can carry out such precepts literally and have much of the spirit of the world left in him; and, indeed, if any person does live true to these doctrines of Christ, the world will have very little to say to him.

And in our Lord's own Life we see these principles lived out to the letter. It would seem, as we study it, that it was the impersonation of all that we characterize as most unworldly. Before He had begun His public ministry He faced and overcame the temptation to bend the knee to the world spirit to save Himself from the shame and humiliation of His Passion; and we see Him afterwards alienate the multitudes by the standard He set before them; escape and hide Himself when they sought to make Him a king, refuse peremptorily to make use of any of those arts that secure popularity. The only hold He cared to establish over His followers is a spiritual hold. His Kingdom must have the free air of Heaven breathing through it; there shall, at any rate in its foundation, be no taint of the spirit or ways of the world.

All the Christian virtues help to engender this spirit, humility, patience, simplicity, penitence, mortification. As these deepen in the soul it seals it with the stamp of unworldliness that is unmistakable.

But such a spirit of unworldliness is not so simple a thing as at first sight it seems. Is it to spring from a contempt of all the concerns of life, and are Christians, the more they imbibe the spirit of the Gospel, to regard with more utter scorn the welfare of the world and of all that is around them? It would seem to be undeniable that the spirit which bids a man if his enemy smote him upon the cheek turn to him the other, or if he take his coat to let him have his cloak also, it would seem that such a spirit must be in irreconcilable opposition to the spirit of competition, upon which all life in this world is based.

Would, then, our Lord, by His teaching the spirit of unworldliness, train His followers in a school in which, so far as the things of this life are concerned, and the dealings with men, they must of necessity be wholly unpractical? Is the perfection of the spirit of Christ one which leads a man to be unbusinesslike, unmethodical in the practical concerns of life, behind the times - so far indeed behind that he is wholly out of touch with them - a person who can be readily tricked by those shrewder men whose characters have been formed under the strain of competition? Is he one who is so absorbed in the loftier thoughts of the Christian aim that when he comes down from his prayers into the streets and thoroughfares, or is obliged to deal with the hard facts of the practical world, he is simply at the mercy of those who if they know nothing of prayer know a great deal about the value of money, and have a quick and unerring way of measuring the men they have to deal with? Did our Blessed Lord intend to place in this practical world an organized body of men whose attitude towards it was to be one of contempt and incompetency, who were to be always at its mercy, never able to deal with it upon its own terms, wholly ignorant of all its concerns, because their citizenship was in Heaven?

We have but to put the question to know what the answer must be. It could not be so. We know that the Church was commissioned to take care of the bodies as well as the souls of men; we know that the first Deacons were ordained in order to relieve the Apostles of some of the pressure of business details, serving tables. In the Apostolic college itself one of the Twelve was the keeper of the purse. Whatever, therefore, our Lord's teaching on the spirit of unworldliness may mean, and, as we have seen, it penetrates all His teaching, it certainly cannot mean imprudence in the practical concerns of life, incompetence to deal with business matters, recklessness in regard to the use and expenditure of money. The unworldliness of the Christian cannot be meant to leave him at the mercy of every clever rogue, nor can we imagine that the more saintly a Christian is the more he is exposed to the chances of being made a fool of.

At the same time it cannot be denied that the formation of the specially Christian virtues and the revelation of faith would have, and as a matter of fact does have, a tendency to lead certain minds to under-estimate the importance of the affairs of life.

The Christian life and those virtues which are distinctively Christian are so nicely balanced that it is very easy for them if over-pressed, however slightly, on one side or the other to lose their balance, and consequently for the person who strives to cultivate them to find that his life has somehow become one-sided. We know as a matter of fact that some religious persons use language about the Christian's relation to this world that is exaggerated and untrue; and it is more than likely that a person in the ardour of the first awakening to the life of faith and the realization of things unseen will do things and say things about the concerns of earth that are unjustifiable and unreal. It is not easy to keep the balance between the claims of this world and the next And it is very natural, however wrong, that one who has been for years engrossed in temporal affairs, and never given a thought to eternity, on awakening to the realities of the other world should rush to the other extreme and neglect as altogether unworthy of his consideration the things that belong to them.

It is an accusation not uncommonly brought against religious people that they are unpractical and lacking in common sense, and that a man is a bad man of business in proportion as he is a good Christian.

And while acknowledging a certain amount of truth in such an accusation, and recognizing that with certain types of character such a danger undeniably does exist, we cannot but perceive at once that our Lord's teaching from first to last provides the remedy against the danger, and that this great defect could only exist in the case of one who pressed certain sayings of our Lord to the neglect of others. The whole idea of our life on earth being a stewardship should make Christians feel their responsibility for all that is entrusted to them; the most material things of life are given to us in trust, and we are responsible for their use and expenditure. The Christian who has grasped this doctrine must feel himself bound to cultivate such gifts as would enable him to put to the best use all that his Master has committed to his care. He would indeed find our Lord utter a very vigorous protest against any such low view of his responsibility in regard to material things in His condemnation of the conduct of the man with one talent: 'Thou wicked and slothful servant, thou oughtest to have put my money to the exchangers, and then at my coming I should have received mine own with usury.' (Matthew 25:26,27)

The spirit of unworldiness, then, as inculcated in the teaching of our Lord, should not, if His teaching is taken as a whole, and one part balanced with another, and as a matter of fact, does not lead His most devout followers to neglect the cultivation of all that vast array of gifts which enable men to manage well the affairs of life, and which equip them for dealing with men in the concerns of business.

Indeed, He has left us in no doubt about the matter, for He spoke one Parable for the express purpose of pressing upon His followers the necessity of cultivating such gifts. He teaches it in the most startling, and, if we might say so reverently, the most daring way.

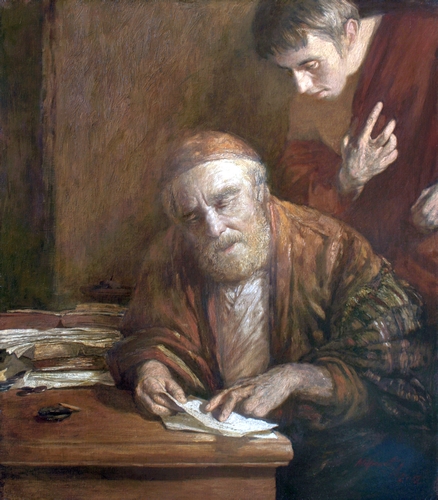

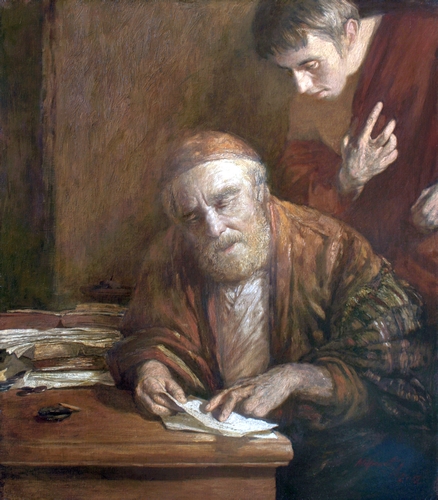

Following immediately upon the greatest and most spiritual of all the Parables, the Parable of the Prodigal, comes the Parable of the Unjust Steward. In this Parable our Lord points His followers to a clever rogue, and says to them, 'You Christians can learn a lesson from such a man as that.'

'The man's deed has two aspects: one, that of its dishonesty, upon which it is most blameworthy; the other, its prudence, its foresight, upon which, if not particularly praiseworthy, it yet offers a sufficient analogon to a Christian virtue - one which should be abundantly, but is only too weakly found in most followers of Christ - to draw from it an exhortation and rebuke to others; just as any other deeds of bold, bad men have a side, that, namely, of their boldness and decision, on which they rebuke the doings of the weak and vacillating good. We may disentangle a bad man's energy from his ambition, and contemplating them apart may praise the one and blame the other. Exactly so our Lord disentangles here the steward's dishonesty from his foresight; the one can only have His earnest rebuke, the other may be useful for the provoking of His people to a like prudence employed about things of a far higher and a more lasting nature.'

Here is a man displaying great talents, clever, resourceful, able to turn everything to account, with his wits about him, ready for any emergency, full of energy and capacity, quick to take in the whole position and rapid in coming to a decision in a crisis. These were not his faults, they were his gifts; and great gifts they are, always meriting praise. The fault was the using such powers for a base and selfish end. But why should not these gifts be used for a good end? If the will of such a man as this unjust steward could be won for Christ, if he could be led to bring all these trained habits of business and natural wit to lay them at His Feet, instead of using them for such unworthy ends, what service he could render to His Kingdom, and what a character would be his!

'The children of this world are in their generation wiser than the children of light.' The children of light do not lay sufficient store upon such gifts. Let them learn from this unscrupulous but clever thief that the talents he is using for destruction may be used for edification.

Our Lord thus refers His followers to a class of persons whose gifts there is a tendency with some of them to despise, and He points out that there is a good deal in such a man that deserves imitation. The training that even an irreligious man gets in the world is not to be ignored. It is in itself, so far as it goes, good. The effect of such discipline and competition is to produce great gifts which would prove of incalculable service to the Children of Light. The supernatural graces of the Christian do not do away with the need of the natural virtues of the man. The grace of God and hours of prayer will not enable us to keep our accounts right unless we take the trouble to learn book-keeping. The zeal of Saint Paul or the asceticism of Saint Anthony will not dispense with the necessity of paying our bills and answering our letters. Indeed we might be pardoned for doubting if such zeal and asceticism were not rather forms of self-deception if the ordinary duties of life were neglected. Yet there is no doubt the danger of setting such store upon the supernatural graces as to lead to the neglect or the slighting of the natural. The one can never atone for the neglect of the other. 'These ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone.' (Matthew 23:23) Those who are like Peter on the house-top, wrapped in heavenly visions, must answer to the knock at the door, the intrusion of the practical life of action if they are ever to understand the full meaning of their visions - unless, of course, in the case of those who are called apart from the outward life of action by a special vocation.

The Parable, then, is meant to correct the mistake of those who realizing very highly the value of the supernatural virtues are in danger of slighting the natural.

But it corrects a further aggravation of this mistake which is not uncommon, the supposition, namely, that certain practical business habits must take some of the lustre off heaven-born virtues. Indeed it goes much further; it bids us, on the authority of our Lord Himself, balance the spiritual side - if I may so call it - of the Christian virtues by the practical.

Humility is no doubt a great Christian grace, but if humility unmans a person and makes him incapable of holding his place with men, it is a spurious humility. Humility is quite compatible with unyielding determination in the affairs of this life as truly as of the other. The Christian does not compromise his humility in the slightest degree by holding his own in matters of business, nor does it prevent him from taking a proper estimate of the men he has to deal with. Meekness is one of the special characteristics of our Lord in which He called upon all His followers to imitate Him; but meekness is not a timid yielding of judgment and place to every comer. If there never was one so meek as our Lord, there never was one more unyielding in matters of right and wrong, never one whose words and bearing were less timid meekness, therefore, does not unnerve a man or expose him to being made the dupe of every unscrupulous person he has to deal with. Heavenly-mindedness enables one to despise the riches of this world, but this does not mean that it makes a man ignorant of the value of money; on the contrary, the person who holds his heart aloof from earthly possessions is likely neither to over-estimate nor to under-estimate their value, but, looking upon all as a trust from God, to develop in the highest sense of the word a keen eye for business, inasmuch as he knows himself to be but the steward of another's possessions.

Bring, then, your humility into the street, into the market place, into the office, and test it by seeing how far it incapacitates you for your work, and see if you cannot round it off by the practical work-a-day facts of life. Do not be afraid; it will not be soiled by contact with all this earthly dross; it thrives there, it becomes vigorous and healthy; it will shine all the brighter in that apparently uncongenial atmosphere, and it will show you a side of it that you never knew before - a courage amounting almost to daring, an undaunted pluck where less humble men hold back in fear, a firmness altogether supernatural, yet so practically useful that it gives its possessor at once an advantage. Yes, the practical side balances, develops, and perfects the spiritual. A humility that can only thrive in the cloister or the closet cannot be the Christian virtue which is meant for all. Indeed, we may believe that the most humble dweller in the cloister, if he were sent forth from it by God to enter for a time into the concerns of business, if he were truly humble, would surprise men by showing that he had an amazing power of taking care of himself, for the training ordinarily to be gained in the world is given in extraordinary ways for special vocations.

And it is the same with all the Christian virtues: the most refined and the most delicate, they thrive in the boisterous and stormy ways of the world. Do not keep them for the closet; bring them out and test them in the street

That patience that was getting just a touch of weakness, a readiness to give in, in some matter of duty, rather than risk a fall - look at it now, in the noise and struggles of a public life; see how quickly it is ridding itself of every remnant of that weakness that would have been its destruction; it is now matured to its proper growth, and shows a strength that is only equal to its gentleness.

It is in the formation of the practical virtues that these rich effects of Christian character are developed and matured. Neglect the natural virtues of the practical life and the others will become weak and morbid. Such appears to be the bracing doctrine of this Parable. It gives a note of warning to religious people that is not unnecessary. Look, it says, at the wit and cleverness and the power of taking care of himself of this unscrupulous man, transfer all these gifts that he has shown to the Christian character, and instead of suffering from these earth-born gifts they will perfect the heavenly. The more distinctively Christian graces, if sublimated, and separated from the natural virtues, become weakened and diseased. The most delicate of them is far more robust than you imagine. Go out with them into all the thronged activities of life, where you have to deal with men and fight your way, and behold the natural virtues developed in contact with all these sordid and unspiritual things will rise up and crown the gifts of grace, and shew you what they are capable of.

- text taken from Practical Studies on The Parables of Our Lord, by Father Basil William Maturin