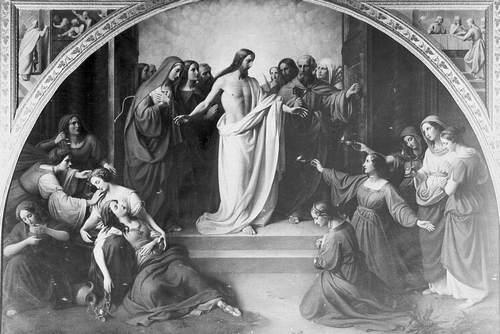

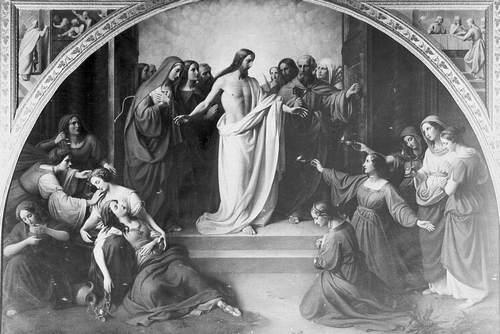

The Ten Virgins

"Then the kingdom of heaven will be like ten virgins who took their lamps and went out to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish and five were wise. The foolish ones, when taking their lamps, brought no oil with them, but the wise brought flasks of oil with their lamps. Since the bridegroom was long delayed, they all became drowsy and fell asleep.

"Then the kingdom of heaven will be like ten virgins who took their lamps and went out to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish and five were wise. The foolish ones, when taking their lamps, brought no oil with them, but the wise brought flasks of oil with their lamps. Since the bridegroom was long delayed, they all became drowsy and fell asleep.

"At midnight, there was a cry, 'Behold, the bridegroom! Come out to meet him!' Then all those virgins got up and trimmed their lamps. The foolish ones said to the wise, 'Give us some of your oil, for our lamps are going out.'

"But the wise ones replied, 'No, for there may not be enough for us and you. Go instead to the merchants and buy some for yourselves.'

"While they went off to buy it, the bridegroom came and those who were ready went into the wedding feast with him. Then the door was locked. Afterwards the other virgins came and said, 'Lord, Lord, open the door for us!'

"But he said in reply, 'Amen, I say to you, I do not know you.' Therefore, stay awake, for you know neither the day nor the hour." - Matthew 25:1-13

* * *

The Parables of the Ten Virgins and of the Talents were spoken by our Lord on the same occasion, as He sat upon the Mount of Olives with the disciples a few days before His death, and they form a striking contrast, representing as they do the same thing, the Kingdom of Heaven, yet possessing not one single feature in common.

The Talents bring us into the market-place, amidst the most active and exciting scenes of life. It is the place where the strain and pressure, which are to be met with indeed everywhere, are most keenly felt, most vividly seen. The struggle for life is at its highest point There is no room there for anyone who is not wide awake and on the alert; should there be any such, another instantly presses forward and takes his place. Those who enter the market-place enter upon a contest in which all the powers of mind and body are taxed to the uttermost, and quickened. We know the characteristics that are developed there - shrewdness, alertness, industry, practical capacity. Those who can make their five talents produce five talents more, must be men of energy and promptness, men who can take all in at a glance and put all to immediate profit, anticipating every emergency, ready and masterful. A moment's hesitation or indecision and they may fail of putting their master's trust to the best account All the characteristics of the men who get on in the market-place, and who consequently received their Master's approval, are those which belong to the most active condition of life, those which make their possessors successful men of business, men of the world. And it is well to note that the men who did get on, and consequently who must have possessed or acquired these gifts, were those who were greeted by their Master with the words of approval, 'Well done, thou good and faithful servant' The only one who received a stem and awful rebuke was the man whom we might characterize as being in the market-place, yet not of the market-place. Who, though sent into the market-place to develop his talent, was lacking in all the push and energy and quickness necessary to get on there, and was, instead of being practical, an idle dreamer.

It seems a strange place and a strange image to choose to represent the 'Kingdom of Heaven,' the life and work of a Christian, yet the picture is drawn by the Hand of our Lord.

Then we turn to the other Parable, the Parable of the Virgins, and all is changed. The Virgins, with their lamps alight, are slumbering while they wait for the call that is to waken them to meet the Bridegroom. Here all is stillness, silence, repose. What a contrast to the rush and turmoil of the market-place! There is no conflict, no straining, no active work even; no need for any of those characteristics without which life in the market-place would be impossible. Such gifts would be useless here, worse, they would be out of place. The shrewd man of business, full of energy and activity, would be intolerable in the quiet stillness of that dreamy night These Virgins must wait, the workers in the market-place must act The more patient they are in waiting, the fitter they are for their place. They have but to keep their lamps alight and tarry till the Bridegroom come. They cannot hasten his coming by one moment; the time rests with Him, not with them. They cannot go into the market-place if they would, their business is to wait that they may be ready when He comes, at midnight, at cockcrow, or in the morning. There is no work that they could offer to Him that would atone for their not being in their place to greet Him at the moment that He comes. The chief characteristics of the Virgins therefore which best fit them to fulfil their office in life are patience, quiet endurance, inaction without sloth, a power of waiting without getting restless or losing interest Outwardly a silent stillness and passivity, inwardly a keen watchful interest and alertness. Strange contrast in all - in life, in character, and in judgment In the one case the servant is judged and condemned because he did not work; in the other, the Virgins are condemned because they did not watch. There seems at first sight to be no point of contact in these two pictures of the Kingdom of Heaven, all that strikes us is the completeness of the contrast.

1. We may consider them first, then, as a contrast, representing two different types of life, lives that are markedly different in their characteristics, even in the eyes of men. There are, we know, many different kinds of vocation. It is not a matter of liking, or of choice, or of natural disposition, that is to decide our place in life, it is a divine call. 'As God hath distributed to every man, as the Lord hath called every one, so let him walk.' (1 Corinthians 7:17) That life is most perfect which most perfectly corresponds to God's will, and God has a Will, a Purpose for each separate soul.

But amidst the multitude of vocations there have always been in the Christian Church two forms of vocation more or less marked. In their most distinct forms they are the active and the contemplative, the life of work and the life of prayer. We find them represented amongst the Apostles in the persons of Saint Peter and Saint John, and amongst the disciples of our Lord in Martha and Mary. We read of one to whom our Lord said, 'Go, and sell that thou hast and give to the poor, and come and follow Me,' (Matthew 19:21) and of another to whom He said, 'Go home to thy friends and tell them how great things the Lord hath done for thee.' (Mark 5:19)

But these same forms of life are to be met with in a more or less marked degree everywhere throughout Christendom: those whom circumstances call out to action and service, and those who in the providence of God are more or less removed from the spheres of active work; sometimes through ill-health or the accidental ordering of their lives, sometimes through a more direct call from God. There are not wanting in every age of the Church those who, some in accordance with, some directly against, their natural dispositions, are led more and more to draw themselves away from outward things, and to find their only power of self-protection and of growth in the life of prayer. In such matters none can judge of another as to the question of a higher or lower form of life; that life is the highest for each to which God calls each, it is not a matter of choice. None can find their sanctification in either form of life, if it be entered upon merely from taste or inclination. God calls whom He wills, and we find each form of life in the most unexpected places and under the most unlikely circumstances.

The two types of life, then, we see figured in these two Parables.

The servants to whom the Talents were given were commanded to go out into the world and develop them. It is as though our Lord said to them, 'It matters little where you may happen to be, outwardly your life may have to be lived in the money market, it matters not, so long as, wherever you are, you remember that the Talents which I have entrusted to you are Mine.' The secret meaning and the interpretation of those crowded, active, busy Christian lives, that which enables those who are living such lives not to get swamped and carried away by the tide, is the constant watchfulness over the motive. He who can always say to himself, wherever he may be, and whatever he may be doing, 'I am here to put my Master's Talents to better interest; I am watching all that goes on, with an eye above all things to my Master's business,' he is safe. The character that is formed in the market-place is not what we should ordinarily describe as spiritual. But the character of the man who goes there to do his Master's work is distinctly spiritual. All that would be worldliness, or shrewdness, in the one, becomes part of the equipment of a distinctly spiritual character in the other, for the character is interpreted by the secret force which sets all its machinery in motion; therefore the long-sighted prudence, the power of shrewd and rapid tactical decision, the plodding perseverance, the keen-sighted business capacity, all these in the mere man of business are one thing, in the man who develops these powers in the service of Christ they are a very different thing.

And the Virgins had to keep the lamp of the inner life trimmed, with the steady flame dispelling the darkness. They were to watch. That was their vocation, to wait and to watch, standing as it were upon the threshold of another world, with the sounds of this world hushed, their eyes gazing into the darkness beyond, and their ears stretched to catch the distant sound of His footsteps. 'Their loins girded about, their lights burning, and they themselves like unto men that wait for their Lord when He will return from the wedding.' (Luke 12:35)

The world could ill afford to dispense with either form of life; there is work to be done, and God chooses the workers. But the workers in the active life will soon weary unless they are supported and aided by those who lead the hidden life of sacrifice and prayer, and God chooses those who are to give themselves to each.

Thus we have the pictures of two different types of life and character. Under one or other of these, more or less distinctly marked, all Christians may be ranged. Each has its own place, its own office, its own type of perfection, its own failures, and its own temptation. It is impossible to compare them, the highest virtues of the one would be imperfections in the other, the character developed by each is wholly unlike. We can, perhaps, more readily appreciate the difficulties and temptations of those who are described in the Parable of the Talents, as it is the type of the most ordinary vocation. Here the failure consisted, looked at from the point of view from which we are now considering the Parable, in an entire refusal to recognize the responsibility of life and its powers as a gift from God, for which an account must be given. The man who was condemned, was condemned because he had made no use of his gifts. He came out from the battle of life undeveloped, undisciplined, with what gifts he had unused. He had shrunk from life's struggle and competition, and had sought to pass through it with as little effort and trouble as possible.

And that other life - the life of the Virgins - surely has its terrible trials. How difficult it is, the life of one debarred from active work, shut out in the providence of God from the power even of helping others. All around, the breathless stillness of the silent night; nothing to excite, nothing to distract, nothing to change what may so quickly deteriorate into monotony and mechanical routine, nothing to give the refreshment of variety. The mind must rouse itself to find its interest in the thoughts of Him for whom it waits, or turn inward and feed in morbid fancy upon itself. There is nothing else to which it can turn for distraction or interest All around it is the night, beyond lie all its hopes and the object of its expectations. The eyes weary with looking into the darkness; the ear becomes strained, till it is startled by sounds which are the creation of its own fancy. Yes, the Virgin life of waiting upon the Bridegroom, of always waiting, has its terrible temptations too.

Some are ever girt, and the lamp bums steadily through the long hours of the night, but some grow weary, and let the lamp of the inner life of devotion grow dim, flicker with uncertain movements, and die out One must work, with his eye fixed upon the end - his Master, to whom he must render account; the other must watch with unwearied patience, and unfailing prayer and love.

2. But the two Parables may be considered, again, not as contrasting two different forms of life, but as bringing out different aspects of the same life.

Considering them in this way, the men with the Talents are also the Virgins with the lamps. This must be the case with every true Christian's life. Looked at from one point of view he must work; he must do his duty in that state of life in which God has placed him; he must exercise and develop his talents; he must go out into the busy market-place of life's competition and struggle. Looked at from another point of view, amidst all this bustle and activity, within, in the inmost sanctuary, the soul stands clad in the Virgin's garment, with the lamp alight and trimmed, waiting for the coming of the Bridegroom. While the brains and hands are working, the soul is on its knees.

Take one signal example. Was there ever a life more active and more crowded with work than Saint Paul's? Travelling from one part of the world to the other, founding churches, writing epistles, going hither and thither with unwearied energy: 'In journeying often, in perils of waters, in perils of robbers, in perils by mine own countrymen, in perils by the heathen, in perils in the city, in perils in the wilderness, in perils amongst false brethren, in weariness and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often, in cold and nakedness, besides those things that are without, that which Cometh upon me daily, the care of all the churches.' (1 Corinthians 11:26,27,28) Yet amidst all this activity, verily the life of the man with the five talents in the market-place, what was his real life - his inner life - what does he say of himself? 'This one thing I do, forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth unto those things which are before, I press towards the mark for the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus.' (Philippians 3:13,14) 'I do count all things but dung that I may win Christ.' (Philippians 3:8) There is the Virgin soul, with loins girded about and lamp burning, waiting for the coming of the Bridegroom. All that outward life of unparalleled energy had but one interpretation, and the interpretation is to be found within. It was the inner life of love and devotion to the Person of our Lord that made Saint Paul's life different from that of any other man who might have been the enthusiastic propagator of a cause in which he was interested. The strength, the indomitable strength that thrived upon difficulties, and gained new energy from defeat, owed its existence to the fact of that inner life of silent worship and ministry to a Person of whom he never lost sight

And if that inner life fails, the other must soon fail too. If within the lamp dies out and the Virgin ceases her vigil, it will not be long before the Talent is wrapped in the napkin and buried in the earth; the soul shrouded in inner darkness loses that spiritual sense which keeps alive the feeling of responsibility for gifts which can only be developed to their full in the service of another.

'Nor yet

(Grave this within thy heart), if spiritual things

Be lost through apathy, or scorn, or fear,

Shalt thou thy humbler franchises support,

However hardly won or justly dear.

What came from heaven, to heaven by nature clings;

And, if dissevered thence, its course is short.'

The man who wrapped his talent in a napkin and buried it, looked at in his inner life was a foolish Virgin who took no oil in the vessel and whose lamp had gone out.

But if the servant developing his master's talents must preserve the inner life of prayer, and devotion, and waiting upon Christ, who will deny that the life of the Virgin soul, waiting for the Bridegroom, has also the other side of action and conflict Yes, truly, those whose days are spent on beds of sickness, or upon whom old age has laid its cold hand, and drawn them away from the many interests of life, or who, under the influence of a Divine Call, have left all that they may wait upon Christ in fast and vigil, such persons know, as few others do, the active struggles with the unseen powers of darkness. The less their contact with men, the more awake they become to the direct efforts of the evil one to impede their progress or to deceive them - 'the terror by night.' If their powers are not to be developed in the thoroughfares of the world, they are to be trained by the more searching and unceasing discipline of the spiritual conflict Let them give up that struggle, let them cease to fight the phantoms of their minds, the weariness that at times paralyses every power of thought, the doubts whether they are not altogether deceived, the questionings of God's dealings with them, the coldness that numbs every spiritual faculty, the times of repugnance to prayer and communion with God. Let them give up such struggles as these, and soon the lamp flickers and grows dim. As soon as the will ceases the struggle to develop the Talents, the lamp ceases to burn.

But then come those mysterious words, 'while the Bridegroom tarried they all slumbered and slept.' How are these words to be explained in either interpretation of the Parable which we have been considering? They all slumbered and slept - it was not only the foolish. Nor can we apply the two expressions that are used: one to the wise, 'they slumbered'; the other to the foolish, 'they slept'. Whatever in this matter the wise did, the foolish did also; they all slumbered and slept.

In following out the interpretation of the Parables which we have been considering, sleep would have been fatal. How, then, are we to explain these mysterious words? I think they may be explained in this way.

There is alike in the best and worst a vast part of our nature undeveloped. We do not know ourselves, or what powers for good or evil lie dormant within us; we never shall know till the whole soul and all its possibilities spring into life and wakefulness at the last great cry, 'Behold! the Bridegroom cometh, go ye out to meet Him.' A great part of the nature of everyone of us lies dormant as long as we are in this world. There come in the lives of most men great crises, types and foreshadowings of the last great crisis, which waken a side of their nature of which they were scarcely conscious before. It was so in that great crisis of the Apostles' lives when they came under the influence of our Lord. 'It must have been that their life with Him had deepened the sense of the mystery of their lives. They had seen themselves in their intercourse with Him as capable of much more profound and various spiritual experience than they had thought possible before. And this possible life, this possible experience, had run both ways up and down. They had recognized a before unknown capacity for holiness, and they had seen also a before unknown power of wickedness. Their sluggishness had been broken up, and they had seen that they were capable of Divine things. Their self-satisfied pride had been broken up, and they had seen that they were capable of brutal things; heaven and hell had opened above their heads and beneath their feet They had not thought it incredible when Christ said. "I go to prepare a place for you, and I will come again and receive you to Myself;" and they did not think it incredible when He said, "One of you shall betray Me." The life with Christ had melted the ice in which they had been frozen, and they felt it in them 'either to rise to the sky or to sink to the depths.' Or, again, 'Look at Adam with the forbidden apple. Is it only that one sin which terrifies him and makes him dread the coming of God, which had been once the joy of the garden day? Is it not that, pressing up behind that sin, he sees the long procession of sins which he and his descendants will commit A pure honest boy cheats with his first little timid fraud, and, on the other side, the bad side of him, the door flies open and he sees the possibility that he, too, should be the swindler whose heinous frauds make the whole city tremble. The slightest crumbling of the earth under your feet makes you aware of the precipice; the least impurity makes you ready to cry out as some image of hideous lust rises before you: "Oh, is it I? Can I come to that?"'

Who could have told of the dormant powers of devotion and love to our Lord that lay slumbering in the breast of Saul of Tarsus on his way to Damascus, only waiting for Christ to come into his life to waken them into activity? Or who could have seen the possibilities of purity and Divine love that lay dormant in the Magdalene possessed with seven devils? Or, on the other hand, who could have foreseen the depths of baseness and treachery that were dormant in Judas when he left all and followed Christ? Yet there it all was. Who could have foretold the dormant powers of cruelty and ingratitude that slumbered in Jerusalem a few weeks before Good Friday, which were to be wakened when the direct question was put to a careless and fickle crowd, 'What shall I do with Jesus that is called Christ?'

These were moments of wakening, but how much more still slumbers within? Indeed, is it not true that the most active and energetic, whether for good or evil, are but half awake in this life compared with the powers that they will exercise in the life beyond the grave? We are constantly wakening up to a sense of possibilities unfulfilled, of ideals unrealized, of a power of love and hate of good and evil whose force and intensity we cannot measure.

And thus we may say that the most active in the market-place is, after all, as compared with what one day he may become, like a Virgin whose lamp is alight, and who, while waiting, slumbers till the Bridegroom's coming rouses her into perfect wakefulness. Or, on the other hand, the sluggard who will not face life's responsibilities and demands, is like the sleeping Virgin whose lamp is fast dying out, and who is by the Bridegroom's call wakened to find herself deprived of what little was left her, and for ever shut out from the possibility of development in the darkness that must shroud her eternally.

We do sometimes get glimpses of what a revelation that last complete awakening will be. Christ comes now by the cross or by some great trial into a family, and we are wholly unprepared for the revelation of character that is displayed. How often at such times the one least thought of comes to the front and discloses powers of self-sacrifice and endurance that surprise us; and another, from whom we expected better things, shows a selfish and cowardly nature, hitherto unawakened, dormant, but, perhaps, quite unknown to the person who exhibits it! The persecutions that beset the Church in its youth were, verily, the going forth of the cry, 'Behold, the Bridegroom cometh.' And what revelations they made! How the spirit of the martyrs often lay dormant under a light and easy exterior, and the spirit of an apostate in a character that seemed to men earnest and devout.

We need, therefore, to watch the tendencies that show themselves from time to time in us, to study carefully and seriously the revelations that sudden and unexpected trials manifest to us, that we may not in the last moment of life, at the cry that calls us forth, whether we will or not to meet the Bridegroom, waken up for the first time to realize that we are altogether different from that which we had believed ourselves to be.

- text taken from Practical Studies on The Parables of Our Lord, by Father Basil William Maturin

"Then the kingdom of heaven will be like ten virgins who took their lamps and went out to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish and five were wise. The foolish ones, when taking their lamps, brought no oil with them, but the wise brought flasks of oil with their lamps. Since the bridegroom was long delayed, they all became drowsy and fell asleep.

"Then the kingdom of heaven will be like ten virgins who took their lamps and went out to meet the bridegroom. Five of them were foolish and five were wise. The foolish ones, when taking their lamps, brought no oil with them, but the wise brought flasks of oil with their lamps. Since the bridegroom was long delayed, they all became drowsy and fell asleep.