The Lost Piece of Silver, The Lost Sheep and The Prodigal

So to them he addressed this parable. "What man among you having a hundred sheep and losing one of them would not leave the ninety-nine in the desert and go after the lost one until he finds it? And when he does find it, he sets it on his shoulders with great joy and, upon his arrival home, he calls together his friends and neighbors and says to them, 'Rejoice with me because I have found my lost sheep.' I tell you, in just the same way there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous people who have no need of repentance.

So to them he addressed this parable. "What man among you having a hundred sheep and losing one of them would not leave the ninety-nine in the desert and go after the lost one until he finds it? And when he does find it, he sets it on his shoulders with great joy and, upon his arrival home, he calls together his friends and neighbors and says to them, 'Rejoice with me because I have found my lost sheep.' I tell you, in just the same way there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous people who have no need of repentance.

* *

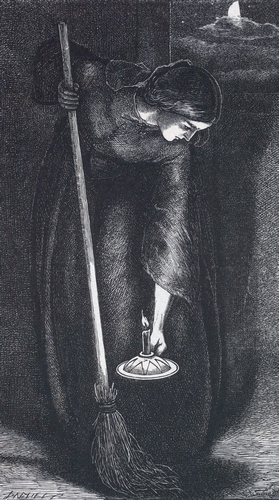

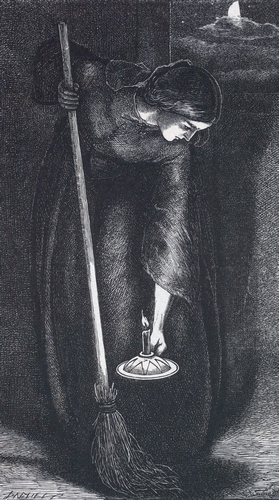

"Or what woman having ten coins and losing one would not light a lamp and sweep the house, searching carefully until she finds it? And when she does find it, she calls together her friends and neighbors and says to them, 'Rejoice with me because I have found the coin that I lost.' In just the same way, I tell you, there will be rejoicing among the angels of God over one sinner who repents."

* *

Then he said, "A man had two sons, and the younger son said to his father, 'Father, give me the share of your estate that should come to me.' So the father divided the property between them.

After a few days, the younger son collected all his belongings and set off to a distant country where he squandered his inheritance on a life of dissipation. When he had freely spent everything, a severe famine struck that country, and he found himself in dire need. So he hired himself out to one of the local citizens who sent him to his farm to tend the swine. And he longed to eat his fill of the pods on which the swine fed, but nobody gave him any.

Coming to his senses he thought, 'How many of my father's hired workers have more than enough food to eat, but here am I, dying from hunger. I shall get up and go to my father and I shall say to him, "Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I no longer deserve to be called your son; treat me as you would treat one of your hired workers."' So he got up and went back to his father.

While he was still a long way off, his father caught sight of him, and was filled with compassion. He ran to his son, embraced him and kissed him. His son said to him, 'Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you; I no longer deserve to be called your son.'

But his father ordered his servants, 'Quickly bring the finest robe and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Take the fattened calf and slaughter it. Then let us celebrate with a feast, because this son of mine was dead, and has come to life again; he was lost, and has been found.' Then the celebration began.

Now the older son had been out in the field and, on his way back, as he neared the house, he heard the sound of music and dancing. He called one of the servants and asked what this might mean. The servant said to him, 'Your brother has returned and your father has slaughtered the fattened calf because he has him back safe and sound.'

He became angry, and when he refused to enter the house, his father came out and pleaded with him. He said to his father in reply, 'Look, all these years I served you and not once did I disobey your orders; yet you never gave me even a young goat to feast on with my friends. But when your son returns who swallowed up your property with prostitutes, for him you slaughter the fattened calf.'

He said to him, 'My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours. But now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.'"

- Luke 15:3-32

* * *

One of the great works of Revelation is to interpret man to himself We are ever striving to understand the mystery of our own being, but we are never able to get far beneath the surface; the light that Revelation throws upon the mystery must, if it is true, explain some of those difficulties which we are ever conscious of feeling in our daily experience. The two-fold knowledge coming from two different sources must harmonize in our practical daily life; as we live and study it, we see it from one point of view, in Revelation we see it from another. The light that is given us in Revelation is meant to interpret some of those things which experience knows, but cannot explain.

One of the most common of these experiences is the restlessness of human nature and its dissatisfaction with all earthly things. Men strive for one thing after another, and when it is gained they are not content, they must have more. 'A spark disturbs out clod,' and fills us with a feverish restlessness that no earthly remedy seems able to cure.

Now, Holy Scripture interprets this restlessness for us, this unceasing dissatisfaction with what has been acquired. It tells us that man was made for God; that whatever else he may be, he is above all things a religious being. Its picture of human life is a vivid picture of life such as we know and see it; it is the most intensely human of all books, but behind all its pictures stands one fact interpreting and explaining them all - man cannot get on without God. The fall was a fall from God, all his troubles arise from setting God aside; his only real failure is a spiritual failure, his restoration is a spiritual restoration.

Scripture opens with a picture of man in the peace and joy of a life near to God, then sin enters and disturbs this close relationship which was the secret of all his happiness; the gates of Eden are closed upon man in rebellion against God. Scripture closes with man restored to his peace in the vision of God: 'The Tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell with them and they shall be His people, and God Himself shall be with them and be their God, and God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes: and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.' (Revelation 21:3,4) 'He that overcometh shall inherit all things; and I will be his God, and he shall be My son.' (Revelation 21:7) That is the highest hope that Revelation inspires: that sinful man can return to God. This is the Gospel; the glad tidings of great joy. Between these two pictures of happiness forfeited and happiness restored, is the history of a long, wild, passionate struggle, now in one way, now in another, to get back that happiness which men felt they ought to have; and in the midst of this endless struggle, God is seen striving to make Himself heard and known, sending failure, suffering, dissatisfaction, and calling to him, 'O man, thou wert made for God, and thy heart is restless till thou find thy rest in Him.'

And this appeal of God to man of course reached its climax in the Gospel. There God Himself is revealed, coming to show man the secret of his restlessness and the key to his happiness - 'Come unto Me all ye that travail and are heavy laden and I will give you rest;' 'I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life.' The veil is lifted up and men are allowed to see Him in Whose love alone they can find rest.

But the Incarnation did more than this: it showed the world that not only was it impossible for it to find rest and true happiness apart from God, but it showed it also that in some mysterious way the Heart of God was restless in its longing for man. If the meaning of all the strange restlessness of human life lay in its unconscious search for God, this restlessness has its counterpart in a mysterious way in the Being of God Himself. If the heart of man was crying out in inarticulate yearnings, 'My soul is athirst for Thee, my flesh also longeth after Thee,' the heart of God cried out, 'How can I give thee up, O Ephraim, how can I deliver thee, O Israel, My heart is moved within Me, My repentings are kindled together.'

This attitude of God towards man the Incarnation did not create, it revealed. It showed God's response to man's unutterable need. What a revelation it was; how different from what men thought! They looked up to Heaven in fear; they sought to assuage the wrath of the offended Deity by the most costly sacrifices; 'the fruit of the body for the sin of the soul.' They did not know that the God whom they sought merely to propitiate was yearning for their love, nor that the secret object of all their longings was that unknown God Himself.

Now, these two thoughts, while they are constantly brought out in all our Lord's life and teaching, are developed with special beauty in the three parables which follow one another in the fifteenth chapter of Saint Luke. They unfold, in an ever-ascending scale of intensity, the deepest mysteries of the life of man and of the Being of God. They are, indeed, the Gospel in epitome. In them man is shown under different forms the secret of his own life, and that which above all things he needs to know and cannot find out for himself about God. These two thoughts run through the three parables, linking them together and bringing out the same great truths in ever-clearer lines: 1. God's need of man; 2. and man's need of God.

1a. In the first Parable, God's tender love towards sinful man is described under the image of a shepherd's care for his wandering sheep. The sheep have passed into the fold, safely housed for the night, and as the shepherd turns homewards he hears the bleating of one sheep straying upon the moors. There is but one thought, he must go after it till he finds it, he cannot leave it to wander and be lost; there is at once the feeling of compassion for its helplessness, it cannot find its way unaided; and the sense of ownership, it belongs to him, he cannot afford to lose it The sheep straying away further and further from the fold in its vain efforts to return calls out all the care and compassion in the shepherd's heart; it is the appeal of weakness to strength, of ignorance to knowledge.

Such, says our Lord, is God's feeling towards the sinner. He is moved with compassion; the need and helplessness of the soul appeal to Him, as the helplessness of the sheep to the shepherd. There is no room for anger; only for pity and love. The soul is straying further and further from its true rest, it does not understand that it cannot govern itself and go where it pleases, it cannot believe that its only safety is under the guidance of another wiser than itself; it breaks away from the shepherd and the fold and wanders away in forgetfulness or denial of God. And our Lord says all this willfulness stirs the Heart of God not to anger but to pity. While man is scorning Him, God has already gone forth to seek him. It is a striking picture: rebellious man taking his life into his own hands, and living in disregard or defiance of God, getting more and more entangled, and hopelessly losing the way of life. And all this, acting but as a great appeal to the Heart of God to help him. His very defiance, his claim of independence, not calling forth anger and judgment, but only moving God to pity. The soul does not know its need of God; still less does it know God's need of it That undefined sense of helplessness and growing restlessness has its counterpart in the great God Himself; the wanderings of the soul are drawing God after it.

1b. In the second Parable the prominent thought is that which lay in the background of the former one: it is the inherent value of the soul. The woman who had lost one piece of silver out of ten is the poorer for the loss; she cannot afford to lose so much; what she has lost is of too much value to herself; she must for her own sake seek for it.

1b. In the second Parable the prominent thought is that which lay in the background of the former one: it is the inherent value of the soul. The woman who had lost one piece of silver out of ten is the poorer for the loss; she cannot afford to lose so much; what she has lost is of too much value to herself; she must for her own sake seek for it.

Our Lord would show us in this Parable, that in some mysterious way the soul is of such value in His eyes that He, in a mystery, is Himself the poorer for every soul that is lost. If we do not feel any need for God, He does need us. What for, we can scarcely form an idea. Our whole history is not disclosed on earth; we only know that with an immense outlay of suffering and trouble God seeks for each lost soul, as the woman for her lost coin. Uninteresting and monotonous as your life may seem, it is of extraordinary interest in the eyes of God. He needs it; He will leave no means untried to regain it. Life is looked upon as a very cheap thing by men on earth; we sell ourselves for very little. Not so with God; anyone of us, the poorest, the most uninteresting, sets Him searching till He finds it.

It has been said, 'Men sometimes seem to suppose that God is not alive to their dangers, but needs to be aroused to take a livelier interest in their condition, and to help them in their strivings against evil. He is thought of as sitting coldly watching our passionate and almost despairing struggles to break away from evil and make our way back to a pure and helpful life, as if He were saying, I will let this sinner learn what it is to have strayed from Me. But it is not so. The initiative is God*s, and all that you desire or do in the way of return to righteousness is prompted by Him.' We may not be moved by the thought of God's compassion; well, then, He appeals to our self-esteem. 'Even in your pride,' He seems to say, 'you do not set high enough value upon yourself; you are of more worth than you imagine; your failure is My loss.' The Treasury of God is impoverished by the sin of man.

Here, then, we are shown that God comes forth to seek man, not merely out of compassion for his folly, but because He is Himself the poorer if He fails to recover him. The thought in this Parable is in advance of the other; the appeal to man implied in it is stronger, and based upon higher grounds.

1c. In the third Parable the leading thought is God's personal love for the soul. 'Yea, even like as a Father pities His own children.' Our Lord reveals to us the love and longing of God for the soul that has turned away from Him, under the most touching image of human affection. It is, as it were, God's appeal to man for mercy. He tells us that it is He Himself who suffers by the sinner's heartless disregard of Him. The son does not perceive that he is breaking his father's heart by his willfulness and neglect of him. As love always gives an unbounded power to the one who is the object of affection, so the fact of God's necessary love for man puts God, so to speak, in man's power. As the reckless, spendthrift son can bring his father's life down with sorrow to the grave, so in a mysterious way have we a similar power to cause grief to God. The deeper the love, the greater the power that is put into the loved one's hands, and God has put this power into the hands of each of us; because He loves us we can make Him suffer. And what suffering is so keen as that of meeting with disregard, contempt, indifference from the loved one.

Such is the leading thought in this, the greatest of the Parables, the Parable of which all the others are but as the setting. It reverses all our preconceived ideas; it is not we who cry in vain to God, but God who cries to us; we are enjoying ourselves in heartless indifference of the pain which we are causing Him. It is not God who will not be entreated, but we who turn away from Him whose love has made Him our suppliant.

Nothing can exceed the high estimate that man must form of the dignity of his own life, if he grasps what our Lord teaches in this Parable of his power in some mysterious but very real way to give sorrow or joy to God Himself.

These three Parables thus show us in an ascending scale of intensity God's care for the soul that He has created. His compassion for it. His estimate of its value, and His personal love drawing Him to come forth in search for it.

2. But they also show man's need of God. They picture in various ways man's unhappiness and powerlessness when separated from God.

2a. In the first Parable the soul is represented under the image of a lost sheep. The sheep is the type of the most utter helplessness and dependence, without the shepherd's care it cannot live. The Parable depicts the sheep wandering from the fold in search of food, and at last perceiving that it has lost its way. It cannot return by itself, its helpless efforts lead it further from the fold; it can but cry out in its need, not knowing to whom it cries, its cry is but the instinctive utterance of its helplessness. It may be that it is crying out only for its companions from whom it has strayed. But that cry is heard and understood by the shepherd; he knows that the sheep, though it knows not, is crying in truth for him, and that it is not its companions, but he alone who can lead it to the fold.

A sheep wandering on the moors, alarmed by its solitude, wakening the mountains with its cries, lost and alone, such, says our Lord, is the soul that has awakened to the consciousness that it has lost God. It has strayed away in thoughtlessness. There has been no deliberate breach with God, no moment of open rupture, it has simply thought of other things and strayed on intent only upon the moment's enjoyment It does not realize its danger, or how far it is wandering, till it wakens up to find that it has lost the fold, lost the shepherd, lost itself.

Thus sin and complete separation from God may begin in mere thoughtlessness. There is another aspect of sin, indeed, brought out in the third Parable - a deliberate act of rebellion, an open rupture between the soul and God; but this Parable would show us that sin may begin in a thoughtless wandering from the right path, without any malicious intention, that the soul may get carried further and further away by the moment's attraction, till it wakens to find that it has lost God. It had not thought of rebellion, it was only influenced by the desire to satisfy its wants, but it ends in complete separation from Him who is the soul's protector. It has not, like the Prodigal, sunk into the degradation of grievous sin, and gone down to the level of the swine, but it is as far away from its true home, and as little able to satisfy its deepest wants. If it were left to itself it would not be long before it, too, must cry out 'I perish with hunger;' wandering away, attracted by the pleasant pasture, it ends in starvation.

For when it has wakened up to realize that it has lost God, it cannot find the way back, its helpless efforts carry it further from Him; it finds that it has, in truth, lost its way, lost the way of prayer, lost the path of discipline, lost the light of faith. It knows not how to return; the shepherd must come and seek it.

Many a soul that has found itself in such a hopeless and helpless state of separation from God can trace its condition, not to deliberate and malicious sin, but to carelessness, lack of self-restraint, the thoughtless seeking after pleasure. But, however it comes about, the Parable describes in eloquent words the utter helplessness of the soul that has lost God. To lose God is to lose itself, to lose its own way.

2b. In the second Parable the soul is represented under the image of a piece of silver which has fallen from the hand of the woman to whom it belongs, and is lost.

In this Parable one special point seems to be the utter uselessness of the piece of silver when it has been lost by its owner; its value remains unimpaired, but it needs to be in the possession of its owner to be of any use. It is of no use to itself apart from her, it has no power to develop its own usefulness, nor can it understand its own worth. It lies upon the floor of the house of no use to anyone, though it is of such value that if only it were lifted up and restored to its owner it would be at once a source of wealth, not only to the mistress of the house, but to the whole household, its value could be expended upon its adornment While it lies on the floor of the house the whole household is the poorer for its loss, though the fact of its being lost can in no way affect its intrinsic worth.

And it can do nothing towards its own restoration; it can but wait till it is found and lifted up from the dust and restored to its owner's hands - verily, it has no power of itself to help itself.

And, as with the piece of silver, so with the soul - when it falls from the Hand of God it is at once drawn to the earth. The force of the earth's attraction at once draws it down, and in itself it has no power to resist it, it needs another force to counteract the attraction earthward. It falls by its own weight, like any material thing, under the power of that all-pervading force. The woman's hand can hold it up and use it; the gentle pressure of her hand, which seems like a caress rather than a force, counteracts that tremendous power that is unceasingly operating, to draw all things to itself Even while the coin is held by the woman that force is acting, but it is not felt, for the gentle grasp of her hand protects it.

Thus does the unprotected soul fall under the all-attracting spell of the world if it escapes for a moment from the Personal care of God. 'Hold Thou me up, and I shall be safe.' It was never intended to stand alone, it was made to be used by another. The moment it escapes from that other's care, it falls earthward, the two forces pull in opposite directions, the earth draws downward, the woman's hand draws up. The coin can but yield itself to one or other, it cannot hold itself up; if for a moment it escape from the hand of her who holds it, it is conscious at once of being seized by, and held in, the embrace of mighty and irresistible currents that bear it downward.

And once down, it is powerless to rise, the pressure upon it is overwhelming. It lies there, whether by its own weight or by some external spell that paralyses all motion, it cannot tell. There it must wait till the power that, to all appearance, with such consummate ease negatives this tremendous force shall lift it up again.

And no sooner does it fall than it begins to lose its lustre; it is not in its proper place, the dust, and grime, and things of earth gather upon it and tarnish it so that it can no longer be recognized as having any value.

How many a soul has thus fallen from God's care and keeping, and lies powerless beneath the spell of that mysterious attraction that holds it down, and paralyses every effort to rise - the power of the world. There it lies getting more tarnished, less capable of being recognized every day, all its power of being of any use suspended. What might it not do if only it would allow God to use it? So far as God is concerned it is lost, yet still, however completely it may be lost, it can lose nothing of its intrinsic value, and the knowledge of its value sets the woman to work to seek for it. The most earth-stained and earth-bound sinner is still of infinite value in the Eyes of God.

So sin wresting the soul from the hand of God who owns it, casts it to the earth, and incapacitates it from fulfilling its proper functions. The imagery of this Parable shows more deeply than the last, man's need of God. The lost piece of money is more helpless and in a more hopeless condition than the lost sheep.

2c. In the third Parable we are shown man deliberately breaking away from the restraints of his father's home, and taking his life into his own hands without regard to his father's will. He begins with a dream of liberty, and ends a slave. He begins by taking all his possessions into his own hands, and ends a beggar.

2c. In the third Parable we are shown man deliberately breaking away from the restraints of his father's home, and taking his life into his own hands without regard to his father's will. He begins with a dream of liberty, and ends a slave. He begins by taking all his possessions into his own hands, and ends a beggar.

In the two former Parables the beginning of sin is not traced to a deliberate act of rebellion against God, or to an open rupture with Him. The sheep wanders thoughtlessly in search of pasture, and loses its way. The coin falls from the woman's hand and gets lost Doubtless an entire separation from God does often begin in such ways, but these would be far from giving a complete picture of the way in which man loses God and loses himself. In this parable the son makes up his mind to leave his father's house. He said to his father, 'Give me the portion of goods that falleth unto me.' 'Give me my life and my powers into my own hands that I may make what I can of them; I do not want to be dependent on thee, I can manage things better for myself.' He would go into a far country, out of reach of his father's interference and plans for him, and live his life according to his own views. Doubtless he had no intention of doing anything unworthy of himself, he did not mind doing what might be unworthy of his father.

And our Lord shows us that a life planned and lived thus, may end on a level with the beasts. Man refusing to recognize the paternal control of his father, will find himself eventually unable to control himself. There are forces in his nature, when loosed from the restraints of obedience to God, the strength of which he cannot measure; they break loose and enslave the will which refuses to submit to its true Master. He who began life with the determination to follow the free impulses of his own desires and to recognize no restraints but those of his own will, when he had indulged himself to the full, awoke to the sense of his misery, crying, 'How many hired servants of my Father have enough and to spare, and I perish with hunger.'

It would be impossible to draw a picture more true to life than that which is drawn in this Parable, showing the contrast between youth in its gay thoughtlessness and perfect self-confidence certain of its own unfailing resources and self-sufficiency, and the man of mature years, weighed down with bitter experience, disappointed with himself and crushed with the sense of failure, utterly powerless to recover himself, sinking into deeper degradation, yet crying out in self-condemnation and remorse. He sees all creation rejoicing while he is miserable. All other forms of life - the servants in his Father's house - having enough and to spare, while he perishes with hunger.

Such is the end of a life of independence, a life lived without any thought of its true purpose, the Will of God. Man beginning by breaking loose from all the restraints of his father's house, ends by longing to be readmitted if only as a hired servant He cannot govern himself, he ever needs something, and at last, often too late, he awakens to realize that what he needs is God.

In the two former Parables the images that are employed lead the mind to dwell upon the helplessness and powerlessness of the soul to return to God when separated from Him. He is incapable of doing anything in regard to his own salvation, he can but wait till God seeks, finds, and restores. In the first Parable he is crying out, 'I have gone astray like a sheep that is lost, oh, seek Thy servant' In the second, 'My soul cleaveth unto the dust, oh, quicken Thou me.' This is one side. 'We have no power of ourselves to help ourselves.' 'No man can quicken his own soul.'

This is one side, but the third Parable brings out in all its fullness the other side - the action of the will, the resolve to return. 'I will arise.' The three together show us the two sides of Saint Paul's paradox, 'Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God which worketh in you both to will and to do of His good pleasure.' (Philippians 2:13,14) If we were only to read the first two Parables, we should say at once that everything in regard to the salvation of the sinner is done by God - that man has nothing to do. If we were to read the last Parable only, we should conclude that nothing is done by God, but that man himself does everything. The three must be taken together, one supplementing the other, then we learn that God is supreme, and that man is free; that God saves us, and yet that every moment we must accept or reject the salvation He offers; that God seeks, finds, restores, and yet that we must ourselves consciously and actively return to Him, or we never shall be restored at all. Thus, then, the three Parables bring out ever more and more clearly on the one side God's need of man, and on the other, man's need of God.

- text taken from Practical Studies on The Parables of Our Lord, by Father Basil William Maturin

So to them he addressed this parable. "What man among you having a hundred sheep and losing one of them would not leave the ninety-nine in the desert and go after the lost one until he finds it? And when he does find it, he sets it on his shoulders with great joy and, upon his arrival home, he calls together his friends and neighbors and says to them, 'Rejoice with me because I have found my lost sheep.' I tell you, in just the same way there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous people who have no need of repentance.

So to them he addressed this parable. "What man among you having a hundred sheep and losing one of them would not leave the ninety-nine in the desert and go after the lost one until he finds it? And when he does find it, he sets it on his shoulders with great joy and, upon his arrival home, he calls together his friends and neighbors and says to them, 'Rejoice with me because I have found my lost sheep.' I tell you, in just the same way there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous people who have no need of repentance.