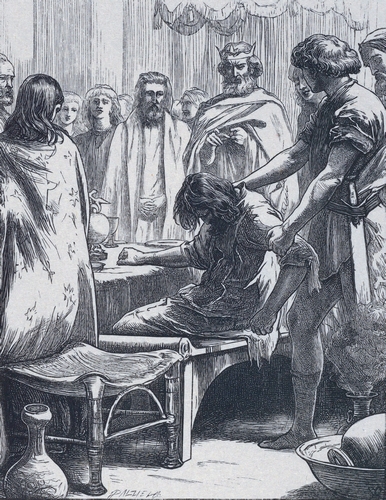

The Guest at the Wedding Feast

He told a parable to those who had been invited, noticing how they were choosing the places of honor at the table. "When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not recline at table in the place of honor. A more distinguished guest than you may have been invited by him, and the host who invited both of you may approach you and say, 'Give your place to this man,' and then you would proceed with embarrassment to take the lowest place. Rather, when you are invited, go and take the lowest place so that when the host comes to you he may say, 'My friend, move up to a higher position.' Then you will enjoy the esteem of your companions at the table. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted."

He told a parable to those who had been invited, noticing how they were choosing the places of honor at the table. "When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not recline at table in the place of honor. A more distinguished guest than you may have been invited by him, and the host who invited both of you may approach you and say, 'Give your place to this man,' and then you would proceed with embarrassment to take the lowest place. Rather, when you are invited, go and take the lowest place so that when the host comes to you he may say, 'My friend, move up to a higher position.' Then you will enjoy the esteem of your companions at the table. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted."

Then he said to the host who invited him, "When you hold a lunch or a dinner, do not invite your friends or your brothers or your relatives or your wealthy neighbors, in case they may invite you back and you have repayment. Rather, when you hold a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind; blessed indeed will you be because of their inability to repay you. For you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous." - Luke 14:7-11

* * *

There are two characteristics common to all forms of organic life:

(1) Each living thing is in itself a unit, and it is throughout the history of its life one from first to last There can be no break in life. The great forest oak is one from the lowest fibre of the root to the topmost leaf of the highest branch. Anything that affects any part of the tree affects it as a whole. The tree is adorned by the blossom on the branch. The tree is injured if a branch be broken off. And it is one from the dawn of its life in the acorn till it falls dead in the forest Its whole history is the history of one life. Anything that affects it in the earliest days of its life may leave its mark upon it till it dies.

This characteristic is common to all forms of life, the lowest as well as the highest. It is as true, nay, in a sense more true, of man than it is of the tree. He is one, and the history of his life from first to last is one whole. There is no breach, no gap in his life. Infant, child, youth and man, it is one and the same person that has passed through all these experiences. You may feel today the effects of what you did or suffered, as it seems to you, almost in another lifetime, it is so long ago. A thought may have sprung into your mind just now that owes its origin to events that happened half a century ago; the continuity, with all that it involves, is unbroken as long as your personal life lasts, and that, we know, lasts for eternity.

(2) The other characteristic is that the greatest changes are effected by the most minute and imperceptible movements; changes so great that the thing to all appearance ceases to be what it was, and becomes something else. Yet it would be impossible for us to say at what moment such a change was completed. The seed is buried in the earth, and under the action of moisture and heat certain movements begin which the eye cannot detect; at last the green blade appears above the soil; it has started, as it were, upon a new phase of its life; and yet the process was so slow and the changes so minute that one could not tell at what moment the seed ceased to be a seed and became a growing plant The chrysalis undergoes mysterious and imperceptible changes beyond the power of anyone to see or to detect; but the moment comes when these changes are accomplished and the chrysalis has ceased to be what it was as the butterfly comes forth into a new and seemingly altogether different existence. Yet, as a matter of fact, the continuity between the butterfly and the chrysalis, and between the plant and the seed, is never broken; the whole life of each is one.

In all these cases the greatest changes are effected by a process so slow and imperceptible that they are only made visible by their results. The mother is surprised to find that her child is no longer a child, but has become a man. There are no sudden leaps in Nature; her work is slow, steady, and lasting in its effects. It is the same, too; with the downward movements of nature: sickness ends in death, life grows weaker as it passes along the pathway of disease, and then it goes out through the doorway of death and enters upon a new state, so different that it passes the power of our imagination to picture what it may be.

In all these developments of life the changes, when they come, are enormous. There is no possible resemblance between the growing blade and the seed, or between the butterfly and the chrysalis, or between the bird and the egg; it has ceased to be one thing and has become another; the door between those two stages is fast closed so that a return to the former stage is impossible. The man can never become a child; the bird can never become an egg; the tree can never again become a seed; and yet at what moment the change is finally effected and the threshold that leads from one form of life to another is crossed, it is impossible for anyone to say, yet when it is passed every eye can see it.

And it is the same with the more complex and subtle life of the soul. There are slow and mysterious movements ever going on within, beyond the power of the eye to see or the ear to hear, often beyond the power of the man himself to detect At last there comes a moment when all these manifest themselves in a change. The man ceases to be what he was and becomes something quite different The whole character has been revolutionized, yet the revolution took place so quietly, the dethroning of one power or passion and the enthroning of another, the loss of interest in one set of things and the awakening of interest in others, that the man who is the subject of all these changes never dreamed of what was taking place within him. 'How changed you are,' says one friend to another, meeting after many years of separation, 'I should not have known you; your interests and tastes and feelings are altogether different from what they were when we met ten years ago.' 'Yes,' he answers, 'looking back over ten years, I did not know how different I was till I met you.'

If, then, such great changes are wrought by slow and almost unconscious movements within the soul, we shall not be wrong, in any great crisis in a man's life, if we look to find the cause lying far back in the past Far down in the depths of the soul there have been silent, unnoticed stirrings, whisperings; the looking upwards or downwards, the longing for what was forbidden, the tampering with temptation, the giving rein to an evil imagination; then the crisis, the fall, or the rise. The mind had long got habituated to evil, the imagination had been captivated, perchance the reason itself seduced, long before the will consented. When finally the crisis came and you stood face to face with that great temptation, you could not resist it; not because at the moment you did not try, but because your whole nature had for so long a time tampered with it. Or, on the other hand, along with an evil life, in the depths of the nature there sprang up a hope, a desire, arid a craving for better things; a gleam in the darkness, the first faint throb of dawn that foretold the coming day. Long years afterwards the crisis came, temptations were met and faced, the will gradually recovered its vigour and you passed from darkness to light. Old things passed away, in very truth all things are become new. It may indeed be possible for the soul with one mighty effort, aided by the grace of God, to leap out of the darkness into light, for man is by nature more akin to the light than to darkness; he is created in the Image of the All Holy not of the evil one; but deterioration must ever be gradual, 'we cannot by one dark plunge sympathize with guilt far beneath us, but gaze at it with recoil, till gradually we fall under the spell of its fascination; but we are capable of sympathizing with moral excellence and purity far above us, so that while the debased may shudder and sicken at the true picture of themselves they can feel the silent majesty of self-denying and disinterested duty.'

It would be a terrible thing were it possible that the discipline and painfully formed habits and the watchfulness of years could give way at any one moment under the stress of temptation without any premonition, any interior relaxation or unfaithfulness preparing the way for such a fall. No, it could not be; if such were possible we might indeed despair. The law of nature as well as that of grace forbids us to believe it possible; habit works with as rigorous a law as any of the physical laws of the universe. A great temptation therefore does but disclose what has been passing within the soul it may be for years before. The moment of temptation is not the moment upon which alone victory or failure depends. One may do his utmost to resist in the moment of temptation, while his failure may have been practically a - foregone conclusion. If Eve had not been tampering with the temptation to eat of the forbidden tree for some time previously she could not have fallen. The moral nature had been imperceptibly relaxing its hold upon God long before the crisis came and she fell. When two armies face one another in battle each no doubt does its utmost in the contest, but victory will depend upon the years of drill and discipline that have preceded. Peter's fall was not the result of a moment in which he was off his guard; it was the outcome of a characteristic defect which we can trace to almost our first knowledge of him, and against which he had been warned by our Lord again and again. Judas's terrible fall was not the result of a moment's great need, or a sudden opportunity presenting itself; it was the result of a deep-rooted fault in his character that had been left unconquered even while he was in the company of our Lord.

This being the case, it is necessary that we should often look backwards as well as forwards. The cause of our greatest moral danger today may not lie in some terrible temptation by which we are at the moment assailed, but in a quiet working of some old habit that has never been entirely broken with. Whether indeed we shall be able to resist the power of the new temptation will probably depend upon the way in which we have been dealing with that old habit.

It is important, therefore, that we should look to the foundations of our character and see that they are sound and secure. We must remember the past We must not forget that underlying our best self is our worst self; beneath the converted life is the unconverted; behind the twenty years of earnest effort and prayer lie those bad, graceless, undisciplined years of boyhood and youth.

But we must consider further not only the foundations, but where they have been laid; what relationship exists between the present and the past, between the spiritual life and those reckless years spent apart from God. On what kind of soil have the foundations of your spiritual life been laid? Our Lord warns His hearers in His first great sermon that some would build, indeed would take His words and build them into their lives, but that they would build without any consideration as to what they were building upon; they would build upon the sand, on the dried-up bed of the winter torrent. This is the difference to which He draws attention between the two classes of His hearers. Some would lay their foundations upon the rock, others upon the shifting sand. Similarly, He warns us against those who, instead of a deep interior change of character, would cover superficially the savage unchanged nature of the wolf with the sheep's clothing. It is not enough to strive now to live a Christian life and to form Christian virtues; we have to consider into what texture already existing we would weave these graces, upon what kind of soil we would build these hopes. In other words, we cannot leave the past out in considering the present and the future.

And so our Lord said, 'When thou art bidden of any man to a wedding, sit not down in the highest room; lest a more honourable man than thou be bidden of him; and he that bade thee and him come and say to thee, Give this man place; and thou begin with shame to take the lowest room. But when thou art bidden, go and sit down in the lowest room; that when he that bade thee cometh, he may say unto thee, Friend, go up higher: then shalt thou have worship in the presence of them that sit at meat with thee.'

In other words He warns those who are bidden to the great Wedding Feast to begin by taking the lowest place; to begin at the very beginning, not to be impatient or ambitious, or in pride to try at once to rival those who fill the highest places; but to go into the lowest place of penitence and reverence and to tarry there until called up higher by the Giver of the Feast.

The Parable teaches us that there is indeed to be progress, that we are not to be content to remain always in the same spiritual condition, but that the advance is to be an orderly one from first to last. That we must begin at the beginning and go on step by step, as we are called upwards by Him who has given the Feast The spiritual life in this respect is like the natural life; it is an organic growth - 'first the blade, then the ear, then the full corn in the ear.' As a tree begins in the seed, so the spiritual life must have its proper beginning, taking root downwards and bearing fruit upwards. It will not do, therefore, to begin too high up. There is the work of the lowest place before we can advance to the highest We have to remove the accumulated rubbish of the past years till we reach the Rock of Christ's Presence within us - that gift of the baptismal life upon which we may lay with security each stone of the new building.

It is necessary, therefore, at first, to keep ourselves back, to learn the principles of the doctrines of Christ before we go on to perfection, and to 'lay the foundation of repentance from dead works, and of faith towards God of the doctrines of baptisms, and of laying on of hands, and of resurrection of the dead, and of eternal judgment.' (Hebrews 6:1,2) That is, not merely a moral but a spiritual and doctrinal foundation, learning what we are to do as Christians, and also what we are to believe before we go on into the higher life of more advanced spiritual experiences. Many begin with doing too much. Saying too many prayers, making too frequent communions, taking for granted that they know all that is necessary to know of the faith, giving out constantly to others before they have really learned to rest upon the inexhaustible source of life within themselves - 'Christ within them the hope of glory.'

It is a good thing, therefore, when anyone feels his religious life unreal and unstable, when he feels that he has committed himself to more than he is really prepared for, or that he is not spiritually up to the standard of those amongst whom he lives and with whom he works, when he is haunted with the sense of spiritual unreality and uncertainty, when he is conscious that he has never really learnt how to pray, or how to examine his conscience, or how to make a good communion, and that he is hazy and altogether uncertain about his belief in regard to the great doctrines of Christianity, that, for instance, he could not tell what he means when he professes his faith in the last six Articles of the Creed, that he does not know what he ought to believe and what he ought not to believe on some of the great controverted questions of the day, or that he has undertaken to help others in matters in which he needs first to be educated himself; it is a good thing that such a person should ask himself seriously and in the Presence of God whether the cause of all this sense of unreality and uncertainty is not to be found in the fact that when he was called to the Wedding Feast and first heeded the call, in other words at his conversion, he was not content to take the lowest place of penitence and preparation, but pushed forward amongst the guests that were privileged to sit in the highest places. May not his case be another example of the seed that fell on the rocky ground and started up quickly, grew too fast, outgrew its strength, had not roots deep in proportion to its growth, and so, when the sun was up, withered away? - when the crisis came failed; when the man was needed who was well equipped and well prepared for some difficult task he had to step aside and let another take his place. 'Give this man place.'

Often in spiritual things we see this: the clever, shrewd, pushing, energetic, but undisciplined man having to give place to the man not nearly so gifted, but who had worked steadily on in obedience to the leadings of our Lord. However it may be in the world, it is certainly true in spiritual things, that it is steady, patient faithfulness to God's leadings, 'the building that hath foundations, whose Builder and Maker is God,' if we may apply these words to the soul, it is such qualities as these to which natural quickness and brilliancy have in the long run to give way. To such persons it is said again and again, 'Give this man place.' 'They that were ready went into the wedding.' Those who, upon being bidden to the wedding, are content to take the lowest place are called up higher and have honour amongst the assembled guests.

And there is but one remedy our Lord implies in such cases. The person who, through pride or impatience, has pushed himself into a position into which he has not been called must leave it 'He must begin with shame to take the lowest room;' that is his only hope, but it is a most real hope. Such a one has learned from bitter experience, and he has learned that pride must have a fall. If he has the courage to begin again, to take altogether a humbler position and a humbler line, and to do what he ought to have done, and to learn what he ought to have learnt years ago, he will not regret it A man who can do that, who, for the sake of being real and thoroughly true, will endure the shame which such a step involves, will eventually have his reward. The giver of the Feast will come to him and say, 'Friend, come up higher; then shall he have worship in the presence of them that sit at meat with him.'

But there is another thought suggested rather than developed in this Parable for those whose danger lies in a very different direction from that which we have been considering. There are some timid and untrustful souls who have taken the lowest places when first called to the wedding and have never gone up higher, although they have been called. They have always feared the risk of undertaking what they are not used to, and of getting out of their groove. They are lacking in courage, lacking in the spirit which is ready to make a venture in obedience to the call of God. And such people certainly are in great danger, for there comes a time when a person can no longer remain where he is, but must go on or deteriorate: he has exhausted the nourishment that is to be found where he is at present 'When I was a child I spake as a child; when I became a man I put away childish things;' the time of childhood comes to an end. There must be growth, movement, development, both inwardly and in the circumstances of one's life. As time goes on it is impossible to cling to the things that were seemly for a child, and therefore there must be advancement When he that bade you to the wedding calls you up higher, you must go up or eventually be superseded. It will not do always to be content with that amount and kind of prayer which you said as a child - you outgrow such prayers or you say them simply as a superstitious form. The monthly, or even less frequent Communions with which you began your spiritual life twenty years ago, and which then were as much as you were capable of receiving with advantage, will not do now. You will not get what you used to get out of such infrequent Communions, your spiritual nature must grow or its powers will degenerate, and, if you do not take heed, may die of atrophy.

There must, then, on the one hand, be a steady movement upwards, guided by the Voice of Him who called each to the Wedding Feast, and, on the other hand, the movement must be regular, orderly, like the growth of an organic life, beginning at the lowest place and not content till you have heard the Voice of Him who first called you bid you come to the very highest place, even into the Presence of the Bridegroom Himself.

- text taken from Practical Studies on The Parables of Our Lord, by Father Basil William Maturin

He told a parable to those who had been invited, noticing how they were choosing the places of honor at the table. "When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not recline at table in the place of honor. A more distinguished guest than you may have been invited by him, and the host who invited both of you may approach you and say, 'Give your place to this man,' and then you would proceed with embarrassment to take the lowest place. Rather, when you are invited, go and take the lowest place so that when the host comes to you he may say, 'My friend, move up to a higher position.' Then you will enjoy the esteem of your companions at the table. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted."

He told a parable to those who had been invited, noticing how they were choosing the places of honor at the table. "When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not recline at table in the place of honor. A more distinguished guest than you may have been invited by him, and the host who invited both of you may approach you and say, 'Give your place to this man,' and then you would proceed with embarrassment to take the lowest place. Rather, when you are invited, go and take the lowest place so that when the host comes to you he may say, 'My friend, move up to a higher position.' Then you will enjoy the esteem of your companions at the table. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted."