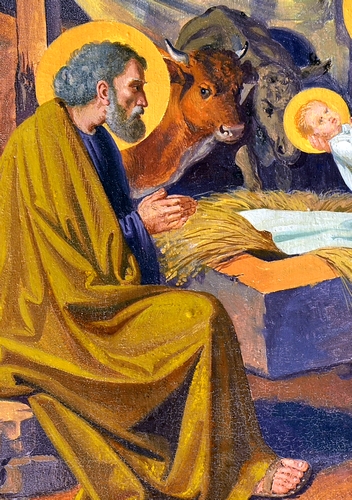

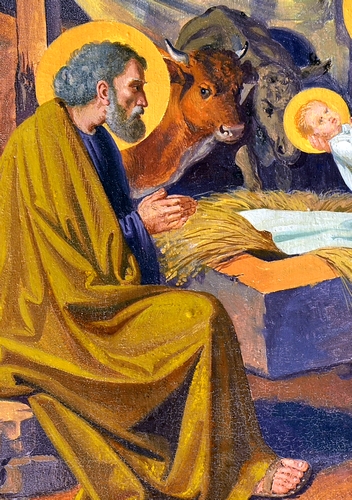

Saint Joseph

Saint Joseph presents us with a similar, yet somewhat different, type of devotion to the Sacred Infancy. We know nothing of the beginnings of this wonderful saint. Like the fountains of the sacred river of the Egyptians, his early years are hidden in an obscurity which his subsequent greatness renders beautiful, just as the sunset is reflected in the dark and clouded east. He was doubtless high in sanctity before his Espousals with Mary. God's eternal choice of him would seem to imply as much. During the nine months the accumulation of grace upon him must have been beyond our powers of calculation. The company of Mary, the atmosphere of Jesus, the continual presence of the Incarnate God, and the fact of his own life being nothing but a series of ministries to the unborn Word, must have lifted him far above all other saints, and perchance all angels too. Our Lord's Birth, and the sight of His Face, must have been to him like another sanctification. The mystery of Bethlehem was enough of itself to place him among the highest of the saints. As with Mary, self-abasement was his grandest grace. He was conscious to himself that he was the shadow of the Eternal Father, and this knowledge overwhelmed him. With the deepest reverence he hid himself in the constant thought of the dignity of his office, in the profoundest self-abjection. Commanding makes deep men more humble than obeying. Saint Joseph's humility was fed all through life by having to command Jesus, by being the superior of his God. The priest, who has most reason to deplore the poverty of his attainments in humility, is humble at least when he comes to consecrate at Mass. For years Joseph lived in the awful sanctity of that which to the priest is but a moment. The little house at Nazareth was as the outspread square of the white corporal. All the words he spoke were almost words of consecration. A life worthy of this, up to the mark of this - what a marvel of sanctity it must have been!

Saint Joseph presents us with a similar, yet somewhat different, type of devotion to the Sacred Infancy. We know nothing of the beginnings of this wonderful saint. Like the fountains of the sacred river of the Egyptians, his early years are hidden in an obscurity which his subsequent greatness renders beautiful, just as the sunset is reflected in the dark and clouded east. He was doubtless high in sanctity before his Espousals with Mary. God's eternal choice of him would seem to imply as much. During the nine months the accumulation of grace upon him must have been beyond our powers of calculation. The company of Mary, the atmosphere of Jesus, the continual presence of the Incarnate God, and the fact of his own life being nothing but a series of ministries to the unborn Word, must have lifted him far above all other saints, and perchance all angels too. Our Lord's Birth, and the sight of His Face, must have been to him like another sanctification. The mystery of Bethlehem was enough of itself to place him among the highest of the saints. As with Mary, self-abasement was his grandest grace. He was conscious to himself that he was the shadow of the Eternal Father, and this knowledge overwhelmed him. With the deepest reverence he hid himself in the constant thought of the dignity of his office, in the profoundest self-abjection. Commanding makes deep men more humble than obeying. Saint Joseph's humility was fed all through life by having to command Jesus, by being the superior of his God. The priest, who has most reason to deplore the poverty of his attainments in humility, is humble at least when he comes to consecrate at Mass. For years Joseph lived in the awful sanctity of that which to the priest is but a moment. The little house at Nazareth was as the outspread square of the white corporal. All the words he spoke were almost words of consecration. A life worthy of this, up to the mark of this - what a marvel of sanctity it must have been!

To be hidden in God, to be lost in His bright light, is surely the highest of vocations among the sons of men. Nothing, to a spiritually discerning eye, can surpass the grandeur of a life which is only for others, only ministering to the divine purposes as in the place of God, without any personal vocation, or any purpose of its own. This is the exceeding magnificence of Mary, that her personality is almost lost in her official vicinity to God. This, too, in its measure was Joseph's vocation.) He lives now only to serve the Infant Jesus, as heretofore he has but lived to guard Mary, the lily of God. He is as it were the head of the Holy Family, only that, like a good superior, he may the more completely be the servant, and the subject, and the instrument. Moreover, he makes way for Jesus when Jesus comes of age. He passes noiselessly into the shadow of eternity, like the moon behind a cloud, complaining not that her silver light is intercepted. He does not live on to the days of the miracles and the preaching, much less to the fearful grandeurs of Gethsemane and Calvary. His spirit is the spirit of Bethlehem. He is, in an especial way, the property of the Sacred Infancy. It was his one work, his single sphere.

He is thus an object of imitation to those souls who have seasons when they are so possessed with devotion to the Sacred Infancy, that it appears fo them impossible to have any devotion at all to the passion, and who are very naturally disquieted by this phenomenon, and distrustful of it. Singularity is always to be distrusted. If we are out of sympathy with the great multitude of common believers, the probability is that we are in a state of delusion. There are, indeed, such things as extraordinary impulses of the Holy Ghost, but they are rare; and even they follow analogies, and follow them most when they seem strangest and most singular. Thus there is no instance of any of the saints having gone through life so absorbed in any other of our Blessed Lord's mysteries as to have disregarded the Passion, or not placed it among their foremost devotions. The prominence given to the Passion in the spiritual life of Margaret of Beaune, especially during her latter years, is a remarkable confirmation of this doctrine.

Yet with some there are seasons - seasons which come, and do their work, and go - during which they seem blessedly possessed with the spirit of Bethlehem, and in those times nothing is seen of Calvary but its blue outline, like a mountain on the horizon. Grace has something especial to do in the soul, and it does it in this way. Saint Joseph must be our patron at those seasons, as having been sanctified himself with an apparent exclusiveness by these very mysteries of Bethlehem, Yet it was not with him, neither will it be with us, a devotion of unmingled sweetness. At the bottom of the Crib lies the Cross; and the Infant's Heart is a living Crucifix, for all He sleeps so softly and looks so fair. From Joseph's first fear for Mary, and the mystical darkness of his tormenting perplexity, to the very day when he laid his tired head on the lap of his Foster-son, and slept his last sleep, it was one continued suffering, the torture of anxiety without the imperfection of disquietude. The very awe of the nine months must have killed with its perpetual sacred pressure all that was merely natural within him; and our inner nature never dies a painless death, as the outer sometimes does. Poverty must have appeared to him in a new light, less easy to bear, when Jesus and Mary were concerned. The rude men and unsympathizing women of Bethlehem were but the forerunners of the dark-eyed idolaters of Egypt, with their jealous suspicions of the Hebrew stranger, while his weak arm was the only rampart God had set round the Mother and the Child. The flight into Egypt and the return from it, the fears which would not let him dwell in the Holy City, and the rustic unkindliness of the ill-famed Nazarenes - all these were so many Calvaries to Joseph. Sweet and beautiful as is the look of Bethlehem, they who carry the Infant Jesus in their souls carry the Cross also, and where He pillows His Head He leaves the marks behind Him of an unseen Crown of Thorns. In truth, the death of Joseph was itself a martyrdom. He was worn out with love of the Holy Child. It was love, divine love, which slew him; so that his devotion was like that of the Holy Innocents, a devotion of martyrdom and blood.

The foundation, therefore, of Joseph's devotion was, as with Mary, his humility. Yet his humility was somewhat different from hers. It was another kind of grace. It was less self-forgetting. Its eye was always on its own unworthiness. It was a humility that for ever seemed surprised at its own gifts, and yet so tranquil that there was nothing i i it either of the precipitation or the ungracefulness of a surprise. He was un selfishness itself, the very personification of it. His whole life meant others, and did not mean himself. This was the significance of his vocation. He was an instrument with a living soul, an accessory not a principle, a superior, only to be the more a satellite. He was simply the visible providence of Jesus and Mary. But his unselfishness did not take the shape of self-oblivion.

Hence his peculiar grace was self-possession. Calmness amid anxiety, considerateness amid startling mysteries, a quiet heart combined with an excruciating sensitiveness, a self-consciousness maintained for the single purpose of an unintermitting immolation of self, the promptitude of docility grafted on the slowness of age and the measuredness of natural character, unbroken sweetness amid harassing cares, abrupt changes, and unexpected situations, a facile passiveness under each movement of grace, each touch of God's finger, as if he were floating over earth rather than rooted in it, the seeming victim of a wayward, romantic lot and of dark divine enigmas, yet calm, incurious, unquestioning, unbewildered, reposing upon God - these are the operations of grace which seem to us so wonderful in Joseph's soul. It was a soul which glassed in its pellucid tranquillity all the images of heavenly things that were round about it. When mysterious graces were showered down upon him, there is hardly a stir to be seen upon his silent passiveness. He seems to take them as if they were the common sunshine, and the common air, and the dew which fell on all men, and not on himself alone. He was like the speechless, silver-shining, glassy lake, just trembling with the thin, noiseless raindrops, while it rather hushes than quickens its only half audible pulses on the blue gravelled shore. It almost seemed as if, joined with his self-possession, there was also an unconsciousness of his great graces, if we could think that great saints did not know their graces as none others know them. He was not a light that shone, he was rather an odor that breathed, in the house of God. He was like the mountain woods in the wet, weeping summer. They speak to heaven by their manifold fragrances, which yet make one woodland odor, like the many dialects of a rich language, as if the fresh, wind-driven drops beat the sensitive leaves of many hidden and sequestered plants, and so made them give out their perfumes, just as sorrow by its gentle bruising brings out hidden sweetness from all characters of men. So it was with Saint Joseph. He moves about among the mysteries of the Sacred Infancy, a shy silent figure. Between the going and coming of great mysteries we just hear him, as we hear the rain timidly whispering among the leaves in the intervals of the deep-toned thunder. But his odor is everywhere. It is the very genius of the place. It clings to our garments and lingers in our senses, even when we have left the Cave of Bethlehem and gone out into the world's work.

His mind was turned inward upon his dread office, rather than outward on the harvest of God's glory among men. This follows from his self-possession. He stood in an official position; but it was only towards God, not towards both God and men, as was Our Lady's case. Hence there was less of the spirit of oblation about Joseph than about Mary. He and God were together. He knew not of others, except as making him suffer, and so winning themselves titles to his love. The sacerdotal character of Mary's holiness was not apparent in him. He was a priest of the Infant Jesus, neither to sacrifice Him nor to offer Him, but only to guard Him, to handle Him with reverence and to worship Him. Like a deacon, he might bear the Precious Blood, but not consecrate it. Or he was the priestly sacristan to whose custody the tabernacle was committed. This was more his office than saying Mass. All this was in keeping with his reserve. It was to be expected that the shadow of the Eternal Father should move without sound over the world. Shadows speak only by the shade they cast, deepening, beautifying, harmonizing all things, filling the hearts they cover with the mute eloquence of tenderest emotions. God is perhaps more communicative than He is reserved. For, though He has told us less than He has withheld, yet how much more out of sheer love has He told us than we needed to know; and what has He kept back except that which, because of our littleness, we could not know, or that which for our good it was better we should not know?

Some saints represent to us this communicativeness of God, and others His reserve. Saint Joseph is the head and father of these last. It is strange that, while saints have often shown forth to men the union of justice and of mercy which there is in God, or the combination of swiftness and of slowness in the divine operations, and others of the apparent contrarieties in God, no saint appears to have ever copied him in the union of communicativeness and of reserve. We find that illustrated only in the Incarnate Word and His Immaculate Mother. Saint Joseph was the image of the Father. The Father had spoken once, speaks now. His unbroken Eternal Word. Joseph needed but to stand by in silence, and fold gently in his arms that Word which the Father was yet speaking. The manifested Word, the outpoured Spirit, of them Joseph was not the representative. They only hung him round with the splendors of Their dear love, because he was the image of the Father. Such does he seem to our eyes, such is the image of him which rests in our loving hearts - mute, rapture-bound, awe-stricken, with his* soul, tranquil, unearthly, shadowy, like the loveliness of night, and the beautiful age upon his face speaking there like a silent utterance, a free, placid, and melodious thanksgiving to the Most Holy Trinity.

- text taken from the book Bethlehem, by Father Frederick William Faber

Saint Joseph presents us with a similar, yet somewhat different, type of devotion to the Sacred Infancy. We know nothing of the beginnings of this wonderful saint. Like the fountains of the sacred river of the Egyptians, his early years are hidden in an obscurity which his subsequent greatness renders beautiful, just as the sunset is reflected in the dark and clouded east. He was doubtless high in sanctity before his Espousals with Mary. God's eternal choice of him would seem to imply as much. During the nine months the accumulation of grace upon him must have been beyond our powers of calculation. The company of Mary, the atmosphere of Jesus, the continual presence of the Incarnate God, and the fact of his own life being nothing but a series of ministries to the unborn Word, must have lifted him far above all other saints, and perchance all angels too. Our Lord's Birth, and the sight of His Face, must have been to him like another sanctification. The mystery of Bethlehem was enough of itself to place him among the highest of the saints. As with Mary, self-abasement was his grandest grace. He was conscious to himself that he was the shadow of the Eternal Father, and this knowledge overwhelmed him. With the deepest reverence he hid himself in the constant thought of the dignity of his office, in the profoundest self-abjection. Commanding makes deep men more humble than obeying. Saint Joseph's humility was fed all through life by having to command Jesus, by being the superior of his God. The priest, who has most reason to deplore the poverty of his attainments in humility, is humble at least when he comes to consecrate at Mass. For years Joseph lived in the awful sanctity of that which to the priest is but a moment. The little house at Nazareth was as the outspread square of the white corporal. All the words he spoke were almost words of consecration. A life worthy of this, up to the mark of this - what a marvel of sanctity it must have been!

Saint Joseph presents us with a similar, yet somewhat different, type of devotion to the Sacred Infancy. We know nothing of the beginnings of this wonderful saint. Like the fountains of the sacred river of the Egyptians, his early years are hidden in an obscurity which his subsequent greatness renders beautiful, just as the sunset is reflected in the dark and clouded east. He was doubtless high in sanctity before his Espousals with Mary. God's eternal choice of him would seem to imply as much. During the nine months the accumulation of grace upon him must have been beyond our powers of calculation. The company of Mary, the atmosphere of Jesus, the continual presence of the Incarnate God, and the fact of his own life being nothing but a series of ministries to the unborn Word, must have lifted him far above all other saints, and perchance all angels too. Our Lord's Birth, and the sight of His Face, must have been to him like another sanctification. The mystery of Bethlehem was enough of itself to place him among the highest of the saints. As with Mary, self-abasement was his grandest grace. He was conscious to himself that he was the shadow of the Eternal Father, and this knowledge overwhelmed him. With the deepest reverence he hid himself in the constant thought of the dignity of his office, in the profoundest self-abjection. Commanding makes deep men more humble than obeying. Saint Joseph's humility was fed all through life by having to command Jesus, by being the superior of his God. The priest, who has most reason to deplore the poverty of his attainments in humility, is humble at least when he comes to consecrate at Mass. For years Joseph lived in the awful sanctity of that which to the priest is but a moment. The little house at Nazareth was as the outspread square of the white corporal. All the words he spoke were almost words of consecration. A life worthy of this, up to the mark of this - what a marvel of sanctity it must have been!