Chapter XII - Death of Saint Anthony

Saint Anthony gave himself up to preaching with his usual zeal. The people, always anxious to hear his words, went in crowds to his sermons. He preached every day during Lent, and his sermons called forth the same admiration as they did during his first mission in 1228. It may be said that the public enthusiasm increased as the holy man's strength grew weaker. The charity which burned within him made him indefatigable. He preached, instructed, exhorted, he heard the confessions of penitents, and very often remained fasting until sundown. But God sustained the courage of His servant by multiplying miracles about him, which by their number and grandeur recall those we have already related.

After the Lenten time the blessed Anthony went through the countries around Padua, preaching in the villages and hamlets which he met on his way, and prolonging the holy exercises of his mission until Pentecost.

In spite of the purity of intention which he brought to all work of the apostolate, he was worn out by his constant occupations in secular matters. This is why he thought of leaving the city and of retiring into solitude, in order to indulge with greater liberty his inclination for prayer and the study of Holy Scripture. He wrote a letter to his provincial asking permission to follow his wish in this matter. When he had sealed the letter, he left it on his table and went in search of a messenger who would carry it to its destination. When the messenger was found the servant of God returned to his cell to get his letter, but it had disappeared. Then he thought he had acted contrary to the will of God, and thought no more of it. Some days afterwards he was much astonished at receiving from the provincial a favorable reply to the request he had made. It is reasonable to believe that an angel, under the appearance of a messenger, had carried the letter to the provincial, in order to satisfy the pious desires of Anthony, and to prove by a miracle that his request was agreeable to God.

For a long time the servant of God had known the moment of his death, and now it was at hand; but he did not reveal it to his brethren lest he should sadden them.

About a fortnight before that event, seated on a neighboring hillside, he looked over the plain, adorned at this season with all the charms of springtime. He cast his eyes over Padua, which was in fullest bloom, and seemed, as it were, seated in the centre of a bouquet of flowers. Then he experienced an interior joy. He rejoiced at the beauty of the situation and at the crown which God had placed on his brow. Turning towards his companion, he prophesied the future glory of the city. He did not say what this glory would lie; still less from whom it would come. Subsequent events have cleared up the mystery.

Campo San Pietro, or Campietro, a small village, situated three leagues from Padua, where he found a hermitage under the protection of Saint John the Baptist, was the retreat in which the great saint resolved to pass the last days of his life. He was received there at the beginning of dime, 1231, by a pious gentleman named Tiso, the lord of Campietro, with the respect which would be given an angel and an envoy from heaven. Thanks to the care of Tiso, three cells were built from the trunks and branches of large walnut trees, one for Anthony, the others for his two companions, Brother Luke and Brother Roger. This was the last earthly dwelling of the wonder-worker. Shut up day and night in his narrow wooden cell, he filled his heart and mind with heavenly contemplation. Not a sound was heard around or about the place, but everywhere eternal peace and quiet; although numerous pilgrims still came to ask both prayers and advice of the saint. The lord of Campietro sometimes obtained a few moments' conversation with him, and he had the distinguished happiness to receive, at the hands of the saint, the habit of the Third Order.

On the thirteenth day of June, about mid-day, at the time when the saint took his repast with his brethren, he sank down and felt himself fainting away. His companions lifted him in their arms and laid him on a bed of branches. But, warned by this signal that his last hour had come, he expressed the wish to be carried to Padua, to the monastery of the Minors, there to die, assisted and surrounded by his brethren. They took him there on a cart, but so great was his exhaustion that when they reached the gates of the city in front of the Arcella, the monastery of the Clares, his companions advised him to go no farther, but to stay in this place where he could more easily find calm and rest. The sick man consented, and entered the hospital where three or four Franciscans resided, almoners and spiritual guides for the daughters of Saint Clare.

As soon as he had regained a little strength he confessed with profound sentiments of humility, and received absolution. Then filled with a joy for which those who stood near him could give no reason, he intoned in a clear and harmonious voice his favorite hymn, "O gloriosa Domina! Hail, glorious Sovereign!" His eyes remained fixed on an invisible object which captivated all his attention. "What do you see?" asked his astonished companions. "I see my God," he answered.

Then the brothers wished to have administered to him the Sacrament of Extreme Unction which takes away the last stains from the soul - we must be so pure to appear before God. The saint answered: "I have this Unction within me; it is not necessary, but it is good, however, to receive it." After he had received the Holy Viaticum, he received the Holy Unction with the most lively faith and the greatest marks of compunction, reciting with his brethren alternately the penitential psalms. He was then silent for about half an hour, when suddenly, in the midst of the sobs of his assistants, he yielded his soul into the hands of God, and slept his eternal sleep. This was on the 13th of June, 1231, on Friday, just a little before sundown. Anthony was then thirty-six years old.

Then the brothers wished to have administered to him the Sacrament of Extreme Unction which takes away the last stains from the soul - we must be so pure to appear before God. The saint answered: "I have this Unction within me; it is not necessary, but it is good, however, to receive it." After he had received the Holy Viaticum, he received the Holy Unction with the most lively faith and the greatest marks of compunction, reciting with his brethren alternately the penitential psalms. He was then silent for about half an hour, when suddenly, in the midst of the sobs of his assistants, he yielded his soul into the hands of God, and slept his eternal sleep. This was on the 13th of June, 1231, on Friday, just a little before sundown. Anthony was then thirty-six years old.

The Friars Minor resolved to keep, the death of the holy apostle a secret as long as possible. They feared the crowds of people would be too great, and the tumult which might follow. But the sad news quickly spread, and in less than an hour the whole city of Padua knew it. Little children, without having been informed by any one, gathered in groups, and ran through the streets of the city crying, "The saintly father is dead; the saintly preacher is dead. Saint Anthony is dead!" This news, proclaimed by the mouths of innocent children, filled the inhabitants of the city with grief. The storekeepers abandoned their shops, and the workmen left their labors; some ran in the middle of the streets inquiring where the saint had died. A vague rumor designated the convent of Arcella as the place where the mortal remains were lying. At once men, women, and children hastened there. Some young men bearing arms from the quarter called the Tete du Pont had already reached there to guard the body and to prevent all disturbance. There was a frightful tumult. In the midst of sobs and tears the people pressed about and jostled each other to see once more him who had been the spiritual father of Padua.

Several religious houses at once disputed for possession of his precious relics. The Clares asked permission to preserve them in their convent. The religious of Saint Mary claimed the body as their property; especially, they said, as Saint Anthony, in dying, expressed a wish to be buried in the convent of Saint Mary. But after many difficulties which seemed insurmountable, it was decided that the body of the venerated father should be transported to Saint Mary's convent.

An immense procession started from the episcopal palace to visit the precious relics. At the head of the procession walked the bishop of Padua, accompanied by all his secular clergy and all the religious orders of the city and its environs. Then came the governor of Padua, the nobility and the magistrates and the delegates of the common people, followed by the multitudes. When the usual ceremonies were ended by the prelate, the procession returned to Padua, the dignitaries and the magistrates carrying the body on their shoulders. The funeral cortege passed through the outskirts, as well as through the principal streets of the city. At length they arrived at the church of Saint Mary Maggiore, which had become the church of the saint.

This was a grand festival for the people and the city; the houses were draped in white cloth, and the way of the procession strewn with flowers. At each step some splendid miracle took place, and, according to the words of the Gospel, "the blind see, the lame walk, and the dumb speak." The church could not contain the multitudes. The people, for the most part, were compelled to remain outside the doors. The bishop officiated, pronounced the absolution, and sealed the tomb in which the relics of the saint rested.

The tomb of the Portuguese apostle was hardly sealed before it became a centre of pilgrimage - the scene of multiplied wonders - and the bishop solicited the Holy See at once for the honors of canonization. It was no small consolation for Gregory IX to bear the recital of the heroic virtues and the splendid prodigies which recalled all the wonders of the primitive Church. The Pope ordered that the judicial information should begin without delay. In about six months the inquiry was ended, and by an exception perhaps unique in the history of the Church, less than one year after the death of the servant of God, in the midst of the pentecostal feasts, on the 30th of May, 1232, the infallible teacher, then at Spoleto, solemnly promulgated the decree of canonization. At length the pontiff intoned the Te Deum, then the antiphon, Doctor optime, thus publicly saluting the eminent doctor, the defender of the divinity of the incarnate Word, the defender of the Real Presence, the apostle of Mary's prerogatives, and the wonder-worker and saint.

And now a new wonder occurred. The feasts of Spoleto were then being celebrated, and a spirit of irresistible joy ran through the whole city of Lisbon. All the bells in the towers, moved by no visible hand, rang out their joyous chimes, and the inhabitants manifested a joy for which they could give no reason. It was not until two months afterwards that they got a clew to the mystery. By a coincidence, in which the finger of God is visible, the bells of Lisbon, the native city of Saint Anthony, were rung at the same time as those of Spoleto, to congratulate the Portuguese wonder-worker.

On the 13th of June, 1232, Padua was ready to celebrate the feasts of canonization. It was just one year to a day after the death of the wonder-worker. The festivities were splendid beyond all description. The people were overjoyed. They were children praising their father; they were captives returning thanks to their liberator.

Along the streets could be seen tapestries and hangings, branches and flowers strewn in profusion, and joy and gladness were on every side. The people stopped and congratulated one another. This was not merely enthusiasm but a kind of delirium prompted by gratitude and by a love which could not be satisfied.

And the same feasts and the same splendors were to be witnessed in Lisbon. Was not Anthony the saint of Lisbon before he became the saint of Padua? By a rare privilege in the life of saints both parents of Anthony assisted at this triumph. happy mother who could count her sou among her protectors in heaven, and behold all the people render him such honor! happy family, so visibly blessed by God!

The reader will remember how displeased the Canons of Saint Augustine were at the departure of Anthony from their convent, and they did not hesitate to manifest their displeasure openly. But Anthony said on leaving them, "When you hear that I have become a saint you will bless God." These words were a prophecy. As soon as he was placed on the altars, the storm of discord suddenly became calm, and the Canons rivalled the Franciscans in their zeal in proclaiming the praises of their former colleague. From this time a sacred bond existed between them which has never been broken. A bond of eternal and reciprocal friendship now unites the two great religious families, and the union has continued for six successive centuries. Each year, on the 13th day of June, a Canon of the Holy Cross from Coimbra goes to Saint Anthony of Olivares, where he pronounces the panegyric of the saint, and presides at all the exercises of the convent. He does this to remind all that from Holy Cross came one of the most beautiful minds of the Middle Ages, and one of the lights of the seraphic Order.

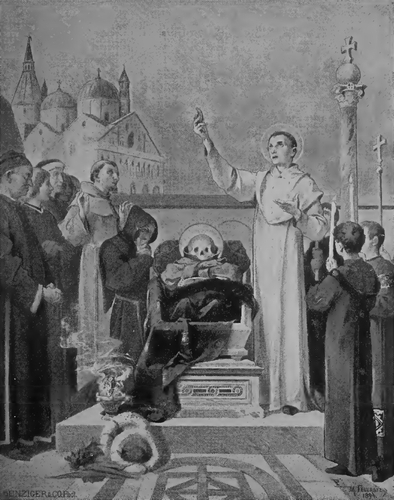

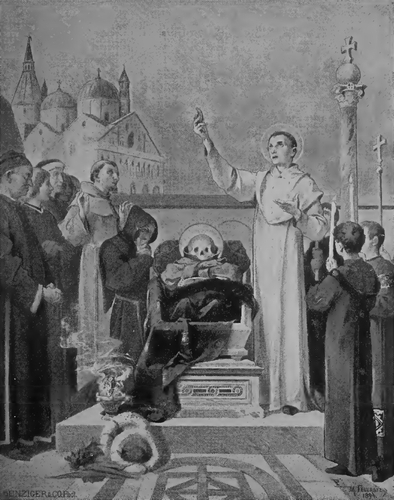

In 1263, thirty-two years after the death of the saint, it was decided to remove his mortal remains from the shrine in the church of Saint Mary Maggiore to the high altar of a new church built in his honor by the Friars Minor. Their minister-general, Saint Bonaventure, was present at the translation of the body, and on opening the coffin it was found that while the body had crumbled into dust, the tongue, which had sung the praises of the Most High and been the means of converting so many, was incorrupt and of its natural color. Moved by the sight of this miracle, Saint Bonaventure exclaimed: "O blessed tongue, which always didst bless the Lord and caused others also to bless Him, now is it evident how highly thou wert esteemed by God!"

In 1263, thirty-two years after the death of the saint, it was decided to remove his mortal remains from the shrine in the church of Saint Mary Maggiore to the high altar of a new church built in his honor by the Friars Minor. Their minister-general, Saint Bonaventure, was present at the translation of the body, and on opening the coffin it was found that while the body had crumbled into dust, the tongue, which had sung the praises of the Most High and been the means of converting so many, was incorrupt and of its natural color. Moved by the sight of this miracle, Saint Bonaventure exclaimed: "O blessed tongue, which always didst bless the Lord and caused others also to bless Him, now is it evident how highly thou wert esteemed by God!"

- taken from Saint Anthony, The Saint of the Whole World by Father Thomas F Ward

Then the brothers wished to have administered to him the Sacrament of Extreme Unction which takes away the last stains from the soul - we must be so pure to appear before God. The saint answered: "I have this Unction within me; it is not necessary, but it is good, however, to receive it." After he had received the Holy Viaticum, he received the Holy Unction with the most lively faith and the greatest marks of compunction, reciting with his brethren alternately the penitential psalms. He was then silent for about half an hour, when suddenly, in the midst of the sobs of his assistants, he yielded his soul into the hands of God, and slept his eternal sleep. This was on the 13th of June, 1231, on Friday, just a little before sundown. Anthony was then thirty-six years old.

Then the brothers wished to have administered to him the Sacrament of Extreme Unction which takes away the last stains from the soul - we must be so pure to appear before God. The saint answered: "I have this Unction within me; it is not necessary, but it is good, however, to receive it." After he had received the Holy Viaticum, he received the Holy Unction with the most lively faith and the greatest marks of compunction, reciting with his brethren alternately the penitential psalms. He was then silent for about half an hour, when suddenly, in the midst of the sobs of his assistants, he yielded his soul into the hands of God, and slept his eternal sleep. This was on the 13th of June, 1231, on Friday, just a little before sundown. Anthony was then thirty-six years old. In 1263, thirty-two years after the death of the saint, it was decided to remove his mortal remains from the shrine in the church of Saint Mary Maggiore to the high altar of a new church built in his honor by the Friars Minor. Their minister-general, Saint Bonaventure, was present at the translation of the body, and on opening the coffin it was found that while the body had crumbled into dust, the tongue, which had sung the praises of the Most High and been the means of converting so many, was incorrupt and of its natural color. Moved by the sight of this miracle, Saint Bonaventure exclaimed: "O blessed tongue, which always didst bless the Lord and caused others also to bless Him, now is it evident how highly thou wert esteemed by God!"

In 1263, thirty-two years after the death of the saint, it was decided to remove his mortal remains from the shrine in the church of Saint Mary Maggiore to the high altar of a new church built in his honor by the Friars Minor. Their minister-general, Saint Bonaventure, was present at the translation of the body, and on opening the coffin it was found that while the body had crumbled into dust, the tongue, which had sung the praises of the Most High and been the means of converting so many, was incorrupt and of its natural color. Moved by the sight of this miracle, Saint Bonaventure exclaimed: "O blessed tongue, which always didst bless the Lord and caused others also to bless Him, now is it evident how highly thou wert esteemed by God!"