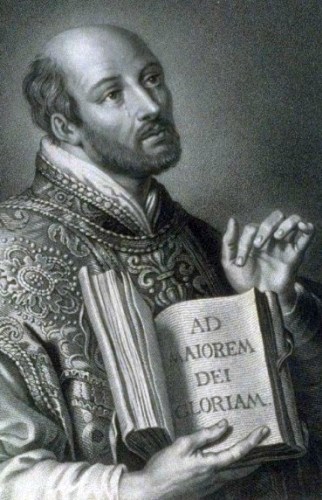

Light from the Altar - Saint Ignatius Loyola, 31 July

Amongst the besieged at Pampeluna about the year 1522 was a man of noble birth. He was not in command, so he could only influence his faint-hearted comrades by his own heroic example and burning woi'ds. In him all hopes were concentrated, upon him all eyes were turned, and he led the forlorn little party into the thick of the fight, fearing no danger, heeding no pain. But suddenly a shot from the enemy's cannon struck a parapet and dislodged a stone, which, in its rebound, broke the young warrior's leg. He fell. The garrison surrendered, and the French flag floated over the battlements. A few weeks after this scene a letter was carried out of the citadel's gates, and an escort party made its way to the castle of Loyola, Ignatius, the youngest son of that noble house, was returning home covered with honors won in the field, but a cripple! The leg was found to be badly set and was re-broken and set again. Fever followed, and Ignatius was brought to death's door. He received the last Sacraments and was given over, but Saint Peter, his own special patron, appeared to him and cured him of his sickness. Ignatius' sufferings, however, were not at an end. To the horror of the vain young Spaniard it was found that a bone protruded below the knee. Such a disfigurement could not possibly be borne. So the doctors were told to saw and cut as might be needful, but to do away with the blemish at all costs. The agony was suffered without flinching. "When this wound had healed, one leg was contracted. Ignatius would limp for the rest of his life, the doctors said. With an indomitable will and pride Ignatius had his limb stretched for hours daily on a species of iron rack. But to no purpose; he was lame from that time forward.

Amongst the besieged at Pampeluna about the year 1522 was a man of noble birth. He was not in command, so he could only influence his faint-hearted comrades by his own heroic example and burning woi'ds. In him all hopes were concentrated, upon him all eyes were turned, and he led the forlorn little party into the thick of the fight, fearing no danger, heeding no pain. But suddenly a shot from the enemy's cannon struck a parapet and dislodged a stone, which, in its rebound, broke the young warrior's leg. He fell. The garrison surrendered, and the French flag floated over the battlements. A few weeks after this scene a letter was carried out of the citadel's gates, and an escort party made its way to the castle of Loyola, Ignatius, the youngest son of that noble house, was returning home covered with honors won in the field, but a cripple! The leg was found to be badly set and was re-broken and set again. Fever followed, and Ignatius was brought to death's door. He received the last Sacraments and was given over, but Saint Peter, his own special patron, appeared to him and cured him of his sickness. Ignatius' sufferings, however, were not at an end. To the horror of the vain young Spaniard it was found that a bone protruded below the knee. Such a disfigurement could not possibly be borne. So the doctors were told to saw and cut as might be needful, but to do away with the blemish at all costs. The agony was suffered without flinching. "When this wound had healed, one leg was contracted. Ignatius would limp for the rest of his life, the doctors said. With an indomitable will and pride Ignatius had his limb stretched for hours daily on a species of iron rack. But to no purpose; he was lame from that time forward.

Months had been passed upon a sick-bed. When he was convalescent, Ignatius, unable to walk or ride, called for some light literature to while away the time. There were no romances in his father's castle, but his attendants brought him what there was - the Life of our Lord, and the: Lives of the Saints. He read them for the sake of distraction, but the works took a stronger hold upon him than he was aware. A struggle began in that grand soul, the winning of which influenced for good the whole world.

Ignatius was physically and morally brave, as we have seen; he was generous, warm-hearted, but passionate, vain, fond of pleasure, ambitious. He wrenched his thoughts away from the splendid example of the saints and turned them back upon the world, his soldier's career so splendidly begun, upon high commands, the love of the fair. But as soon as he took up the books again he became wholly absorbed in them, and moved to admiration. Moreover he noticed that peace came with holy thoughts, unrest and discontent with the worldly ones. This time of deliberation was a critical one to Ignatius, but with Our Lady's help he conquered. She appeared to him in a beautiful vision, and from that time he never looked back. He put his foot on the ladder of self-renunciation and ascended it till it brought him to the gate of Heaven. We know the rest of his career - how in pilgrim's guise he visited Montserrat, hung up his sword before Our Lady's picture, and took a vow of chastity. How at Manresa he mortified his body and endured the assaults of the evil one; how, flooded with heavenly light, he wrote his Spiritual Exercises; how he journeyed to Jerusalem; studied grammar with little boys at Barcelona, philosophy and divinity at Paris; how he spent a year in preparation for his first Mass. Finally, how he founded the Society of Jesus. His is a long life and a very full one. It requires study and time to follow. One thing only may be insisted on here. This great Saint is sometimes spoken of as stern and hard. To himself he was, but to none other. Only read over the list of his good works in Rome, and see if these could have sprung from anything but tender, delicate, overflowing charity. He founded a house for poor Jews; one for penitent women; one for young, innocent girls out of work, and one for orphan children. The sick of the Society, sufferers everywhere were the dearest objects of his care. Nothing was too good for them; others might be stinted, but those in pain, never. No, Ignatius was not hard, else he could not have loved our Lord so well.

Of his great Society suffice it to say that in the Saint's lifetime its missionary priests were found all over the world, in Morocco, in the Congo, in Abyssinia, in South America, in India. Its theologians had seats in the Council of Trent, colleges and universities sprang up in Coimbra, Goa, and Candia. Some of the greatest men of the times called themselves Ignatius' disciples - Francis Xavier, Peter Faber, Salmeron, Lewis da Ponte, Alvarez - to mention but a few.

And this man, who seemed to have moved all Europe, was the humblest, simplest of men. As General of the Society, he might have been seen sweeping, making beds, tending the sick. Only he was contemptible, he used to say. His burning love of God shone in his countenance. Saint Philip Neri, who visited him, spoke of the rays of light that lit up his face. "O God, my Lord, oh, that everyone knew Thee!" he would repeat with tears of devotion streaming down his thin cheeks. "To the greater glory of God" was his battle-cry, his word of command for a step higher. He died in 1556, in his sixty-fifth year. With the Holy Name on his lips and his eyes and hands raised to Heaven, he gave up his soul to his Maker.

Let us learn from Ignatius' blessed lips that prayer that thousands have said after Him: "Receive, Lord, all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and my whole will. You have given me all that I possess, and I surrender all to Your Divine will. Give me only Your love and Your grace. With this I am rich enough."

- taken from Light from the Altar, edited by Father James J McGovern, 1906

Amongst the besieged at Pampeluna about the year 1522 was a man of noble birth. He was not in command, so he could only influence his faint-hearted comrades by his own heroic example and burning woi'ds. In him all hopes were concentrated, upon him all eyes were turned, and he led the forlorn little party into the thick of the fight, fearing no danger, heeding no pain. But suddenly a shot from the enemy's cannon struck a parapet and dislodged a stone, which, in its rebound, broke the young warrior's leg. He fell. The garrison surrendered, and the French flag floated over the battlements. A few weeks after this scene a letter was carried out of the citadel's gates, and an escort party made its way to the castle of Loyola, Ignatius, the youngest son of that noble house, was returning home covered with honors won in the field, but a cripple! The leg was found to be badly set and was re-broken and set again. Fever followed, and Ignatius was brought to death's door. He received the last Sacraments and was given over, but Saint Peter, his own special patron, appeared to him and cured him of his sickness. Ignatius' sufferings, however, were not at an end. To the horror of the vain young Spaniard it was found that a bone protruded below the knee. Such a disfigurement could not possibly be borne. So the doctors were told to saw and cut as might be needful, but to do away with the blemish at all costs. The agony was suffered without flinching. "When this wound had healed, one leg was contracted. Ignatius would limp for the rest of his life, the doctors said. With an indomitable will and pride Ignatius had his limb stretched for hours daily on a species of iron rack. But to no purpose; he was lame from that time forward.

Amongst the besieged at Pampeluna about the year 1522 was a man of noble birth. He was not in command, so he could only influence his faint-hearted comrades by his own heroic example and burning woi'ds. In him all hopes were concentrated, upon him all eyes were turned, and he led the forlorn little party into the thick of the fight, fearing no danger, heeding no pain. But suddenly a shot from the enemy's cannon struck a parapet and dislodged a stone, which, in its rebound, broke the young warrior's leg. He fell. The garrison surrendered, and the French flag floated over the battlements. A few weeks after this scene a letter was carried out of the citadel's gates, and an escort party made its way to the castle of Loyola, Ignatius, the youngest son of that noble house, was returning home covered with honors won in the field, but a cripple! The leg was found to be badly set and was re-broken and set again. Fever followed, and Ignatius was brought to death's door. He received the last Sacraments and was given over, but Saint Peter, his own special patron, appeared to him and cured him of his sickness. Ignatius' sufferings, however, were not at an end. To the horror of the vain young Spaniard it was found that a bone protruded below the knee. Such a disfigurement could not possibly be borne. So the doctors were told to saw and cut as might be needful, but to do away with the blemish at all costs. The agony was suffered without flinching. "When this wound had healed, one leg was contracted. Ignatius would limp for the rest of his life, the doctors said. With an indomitable will and pride Ignatius had his limb stretched for hours daily on a species of iron rack. But to no purpose; he was lame from that time forward.